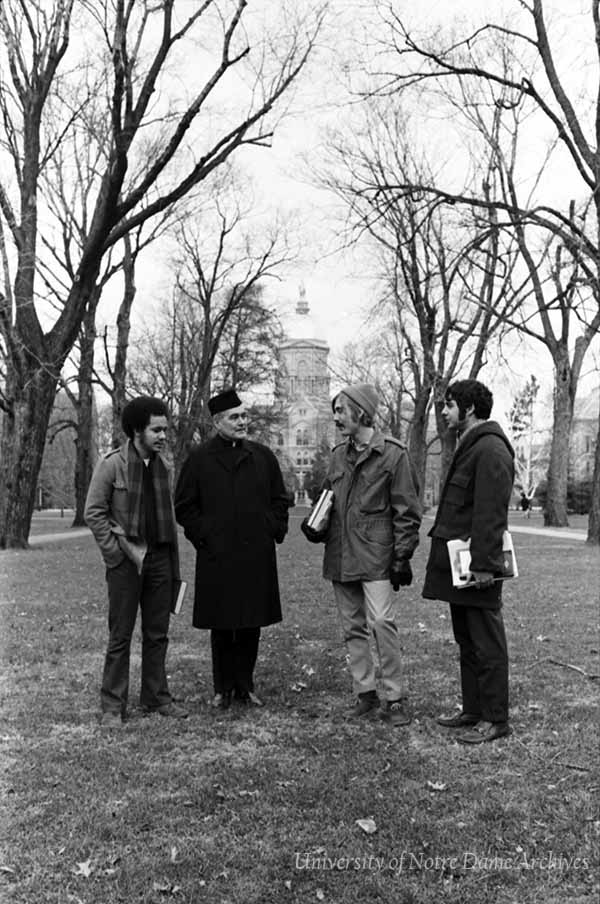

Caption

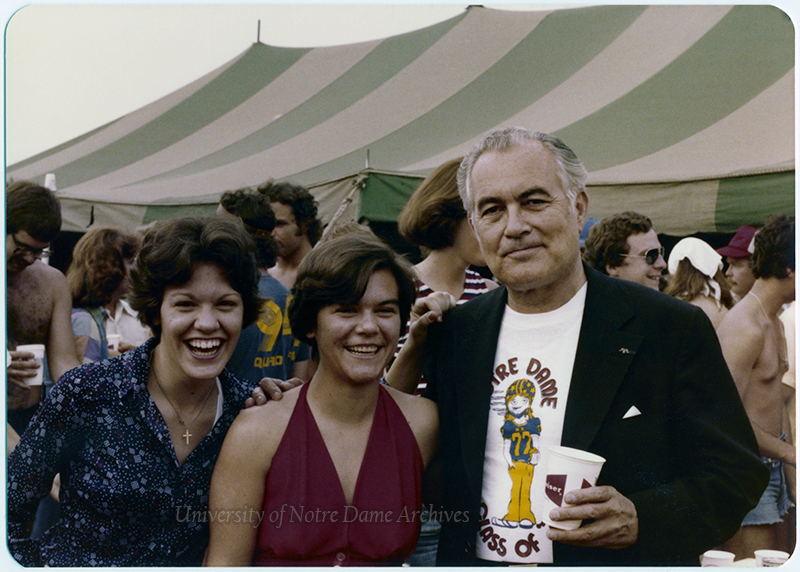

Caption

Source: University of Notre Dame Archives.

Availability to Students

Although Father Hesburgh was on various boards and commissions in the United States and abroad, when he was on campus, he was very much present. Given the number of tasks he must have juggled in his mind, he had the ability to leave everything behind him and be present in the moment. Father Hesburgh noted in his biography,

Highly disciplined by nature and training, I could fly to New York or Washington for a day's work and return that night to Notre Dame. I always preferred the late-evening or nighttime quiet hours, say from 6 or 7 p.m. to 2 or 3 a.m., to get my real work done-to gather my thoughts, to reflect, to do my paperwork, and, not infrequently, to be available to those venturesome students who climbed the fire escape late at night and tapped on my office window for a midnight chat. I maintained an open-door (and open-window) policy, keeping myself available on a one-to-one basis for anyone-student, professor, or administrator-who wanted to see me.

Friend/Advocate

In Father Hesburgh's early days on campus, before becoming an administrator, he was rector of Badin Hall and instructor in the religion department. The young men in Badin were mostly veterans from the Second World War on the G.I. Bill, which allowed them to begin or continue their education free of charge. As these men were generally a bit older, closer to his age, and more mature, Father Hesburgh loosened the restrictions that applied to students as he was able. As Michael O'Brien pointed out in Hesburgh: A Biography,

The university minutely regulated student life. (Some faculty members labeled the university the "Catholic West Point.") Visits to nearby South Bend were strictly monitored; students had to sign in and out of their dormitories; lights went out at midnight, and there were frequent bed checks. Students also had to attend Mass at least three times a week or they lost privileges.

According to Richard Conklin, Notre Dame's chief publicist, in a Notre Dame Magazine article, "He shared the third floor with 80 returned vets. When the lights were shut off at 11 o'clock, his room, 333, quickly filled with students who wanted to continue studying. He did his best to accommodate them." Father Hesburgh helped to form the Notre Dame Veterans Club and became their chaplain.

Source: University of Notre Dame Archives.

Counselor

After the Veterans Club dissolved, Father Hesburgh took on the role of chaplain to the married vets of Vetville and their families. As biographer Michael O'Brien pointed out,

He taught theology during the day and sometimes at night he babysat for a Vetville couple... Working overtime trying to keep the married veterans happy, he counseled those with fragile marriages. ... He kept reminding couples that they probably would never be as poor as they were then, and probably never as happy.

Becoming a counselor to these families led him to design a course on marriage, which many young veterans took and were grateful for.

In September of 1948, Father Hesburgh became the rector of Farley Hall, and was responsible for a few hundred 17- and 18-year-old freshmen. "He concentrated on memorizing the names of all his charges, dealt with them as individuals, and tried to be understanding."

Beginning in 1949, Father Hesburgh assumed more and more administrative work, first becoming executive vice president of Notre Dame under Father John J. Cavanaugh, C.S.C., and then president in 1952. His care and concern for his students never waned, and they knew where to find him. According to Richard Conklin,

When it came to visiting the sick, comforting the dying, celebrating the Eucharist, witnessing marriages and baptizing infants, however, he was as available as he could make himself. The light in his office enticed many a student night visit via the fire escape. Some came to complain, others to go to confession.

Students would go to Father Hesburgh for various reasons, such as when they disagreed with the strict policing of students in the 1950s and '60s, or when they were concerned about their performance in school, or when they simply wanted to talk to someone. Father Hesburgh was known to be a very approachable and kind person. He was known for his ability to drop everything and focus on the moment, so students could tell he really cared.

Source: University of Notre Dame Archives.

Surrogate Parent

Many students recalled Father Hesburgh's interest in their experience as Peace Corps volunteers. Evadna Smith Bartlett remembered Father Hesburgh becoming like a surrogate parent to the young volunteers who were there for training before leaving for Chile. She recalled for Notre Dame Magazine,

We came from across the United States, Catholics and non-Catholics, Notre Dame graduates and alums of other schools, most in our 20s, all eager to serve in Chile-and 45 of us eventually did. Having been instrumental at the Peace Corps' inception, Father Theodore Hesburgh, CSC, had proposed the Chilean project almost as soon as the Peace Corps was conceived.

As soon as the volunteers arrived, Father Hesburgh hosted a welcome reception at the Morris Inn. Bartlett recalled, "We quickly came to realize what an amazing man he was, but we had no idea Father Ted would become a surrogate parent, advocate and teacher and a part of our lives for years so come."

And he continued to be present to the group. He learned everyone's name, where they were from, and what they were studying. He would regularly join them for meals.

Despite his responsibilities, he found time to encourage, challenge, and advise us. ... As a member of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, he discussed the problems and progress in addressing segregation in the nation, pointing out that we would face questions on the issue while in Chile. We did.

Father Hesburgh visited each student at their volunteer site in Chile in order to check in and then contacted all of their families with a report afterward. "He visited each of us in April 1962 at our duty sites, locations spread more than 800 miles from north of Santiago to the Chiloé Archipelago in the south, bringing everything from sewing patterns to wool socks." Father Hesburgh continued to keep in touch with the students over the years, and participated in all of the reunions.

As president of the University, Father Hesburgh truly took on the role of father to the students. In one instance in the 1960s, Father Hesburgh got word while traveling that a student was in a bad automobile accident. He diverted his cab driver and missed a flight to be with the student and his parents. In a separate incident, two undergraduate students were involved in a terrible car crash, and Father Hesburgh was there for them and their families. A friend of the students recalled seeing Father Hesburgh as he arrived at the hospital.

At about 2:30 a.m. Fr. Ted rushed into the intensive care unit carrying his suitcase. He had been in Washington, D.C., learned of the accident, and hopped a Greyhound bus to the Maryland hospital. Seeing 'Hesburgh burst in there in the middle of the night gave everyone a terrific lift.'

Years later, the friend, John Twohey, spoke of the incident. "To me nothing better illustrates the sense of community Father Hesburgh instilled in the school's students, administrators, faculty and staff or the pastoral role he so eagerly embraced on and off the campus."

Source: University of Notre Dame Archives.

Peaceful Presence

During the turbulent 1960s, Father Hesburgh remained a peaceful presence for the students. Some disagreed with his stance on allowing students to have interviews with the C.I.A. and Dow Chemical, which produced napalm used in Vietnam. But overall, students respected Father Hesburgh as he gave students a voice, allowed peaceful protest, and encouraged students to visit him to discuss their positions.

Biographer Michael O'Brien wrote about how the students saw him and included a quote from Notre Dame history professor Tom Stritch.

Many students supported him throughout the turmoil. "He's done more for Notre Dame than anybody"; "I've known students to call at his office past midnight and talk with him all night." He earned their trust. Even many of the student journalists who clamored for his resignation knew that he stood for freedom and dignity. "This undercurrent of trust," said Stritch, "this link between Hesburgh and his students never failed him. Moreover, it was based in part on Hesburgh's sympathy with some student causes, much as he deplored their lawless pursuit of them."

Father Hesburgh also mentioned those years in his autobiography.

I always believed that most of the students knew I agreed with them on many issues and that I had a great deal of sympathy for them. I am not sure how well I communicated that, but it was there. I was always available to talk to anyone who wanted to talk, and at any time of day or night.

Generous Spirit

For the most part, Father Hesburgh's salary went to support the Holy Cross order, but he earned extra money from speaking around the country. He was known to be generous with these funds. And often very few knew of his generosity. O'Brien mentioned one instance in Hesburgh's biography, of which one colleague, James Frick, director of development and later vice president for public relations and development, was aware.

Often he helped foreign students with financial problems. When a nun ran out of money to complete her Ph.D. and her religious order couldn't continue to support her, he dipped into his fund and provided her with assistance. "No fanfare," observed James Frick who witnessed the incident. "That was not unusual at all."

Spiritual Father

Carolyn Short, a 17-year-old freshman from St. Paul, Minnesota, called upon Father Hesburgh in the fall of 1973. She was in the second academic class of women to attend Notre Dame. She recalled in Thanking Father Ted, a book authored by the alumnae of Notre Dame and written to thank Father Hesburgh for the gift of coeducation,

Father Hesburgh walked with me to the Grotto and we prayed together. It was quiet, cold, and it was dark except for the soft glow of the candles and the stirring of the fall leaves in the wind. We prayed to the Holy Mother, and Father Hesburgh told me to ask for guidance in this important year.

She would continue to stop in to talk with Father Hesburgh throughout her time at Notre Dame, and later reflected how much these conversations meant to her.

I am quite sure that I was one of hundreds, if not thousands of students that Father Hesburgh touched personally at Notre Dame, but I felt like I was the only one. I never thought myself a leader. Father Hesburgh did. I never thought myself a scholar. Father Hesburgh did. I never thought myself spiritual. Father Hesburgh did. I never thought much about my future. Father Hesburgh made me.

As Father Hesburgh headed into retirement at Notre Dame, he was even more present than he had been while president, waiting in his office on the thirteenth floor of the Hesburgh Library for any who might call upon him.

Each time I am called "Father," I know that the caller owns me, as a child does a parent, and that he or she has a call on me for anything needed, especially compassion and understanding in the spirit of Christian love: loving and serving Jesus Christ by loving and serving all those in need, anywhere and everywhere.

Father Hesburgh, God, Country, Notre Dame

Source: University of Notre Dame Archives.