Caption

Caption

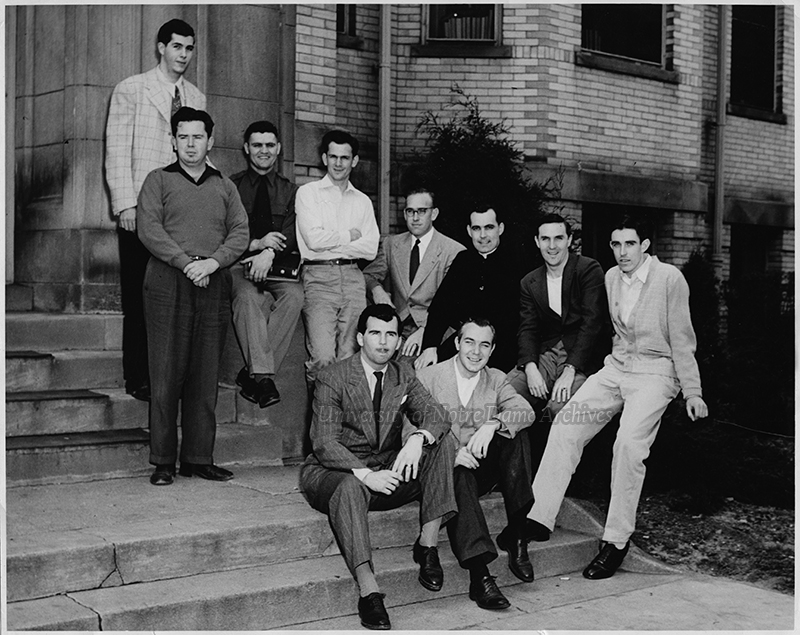

Source: University of Notre Dame Archives.

The Veterans Era: Return to

Notre Dame

The G.I. Bill

The Servicemen's Readjustment Act of 1944 (better known as the G.I. Bill), was signed into law on June 22, 1944 by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. This bill was far reaching, taking into account many of the needs of veterans of the Second World War. For those wanting to return to the workforce but unable to find work, this bill provided unemployment benefits at the rate of $20 per week for one year. Additionally, it provided low-interest mortgages, established veterans hospitals, and strengthened the authority of the Veterans Administration so that it could efficiently assist veterans. To many, the most attractive part of the G.I. Bill was that it gave servicemen the opportunity to return to, or begin to, pursue their studies without charge (up to $500 per academic year), and provided a monthly living allowance while enrolled. Tuition for a day student at Notre Dame in 1944 depended on the area of study, but was on average $380 and, with room and board, was $800. The following academic year, tuition would average $410 and with room and board was $940.

Back on Campus

In early July of 1945, Father Hesburgh returned to the University of Notre Dame, after having been away for eight years. He had just been told by his superior that he would not be a military chaplain as he had hoped because there was a greater need for him on campus. Little did he know that World War II would be over in a matter of weeks, and hundreds of servicemen would be flooding the admissions office to enroll at Notre Dame. Father Hesburgh moved into Badin Hall and became the rector of the young veterans already on campus. Within the next year, veterans would make up nearly seventy-five percent of the student body.

As Father Hesburgh got to know the young veterans in Badin Hall, he learned they had different needs than the typical college student. They were a bit older and had experienced war firsthand. And, as he later reflected in his autobiography, "They were a fine group of young men who studied hard, swapped war stories far into the night, and had an occasional need to let off steam which disrupted everyone around them." It was clear they needed some sort of an outlet, so Father Hesburgh started the Notre Dame Veterans Club and became its chaplain.

Source: University of Notre Dame Archives.

Instructor of Religion

When Father Hesburgh was not attending to the spiritual or social needs of the veterans, he was teaching. One of the first classes he taught was a course on moral theology, with a handful of notecards and what he recalled as a poorly written textbook. He later wrote that the book, Moral Guidance, was "just about the worst presentation of moral theology I had ever seen." The Religion Department at Notre Dame was badly in need of a reorganization. Father Hesburgh was the first in the department to hold a doctorate. Charlie Sheedy, his friend from D.C., would be the second, and within a few years, fifteen to twenty Holy Cross priests would also receive their doctorates.

With the assistance of Charlie Sheedy, Father Hesburgh began working on creating a new class. Father Hesburgh later said, "I ignored the textbook and its minimalist moral approach as best I could, and instead stressed the Christian virtues." In what Father Hesburgh saw as an attempt to improve the curriculum, Father Roland Simonitsch, the chair of the Department of Religion, asked Father Hesburgh and Father Sheedy to write and submit syllabi for new classes. These syllabi would become the basis for new theology textbooks published as The Christian Virtues, by Father Sheedy, and God and the World of Man, by Father Hesburgh.

By 1946, World War II veterans took up nearly three-fourths of the student body at Notre Dame. According to the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, many more than anticipated took advantage of the education benefits throughout the country. "In the peak year of 1947, Veterans accounted for 49 percent of college admissions. By the time the original GI Bill ended on July 25, 1956, 7.8 million of 16 million World War II Veterans had participated in an education or training program."