Caption

Caption

Source: University of Notre Dame Archives.

The Seminary: Abroad

Rome

On September 25, 1937, friends Tom McDonagh and Ted Hesburgh, and about eight other men from the Eastern United States and Canada, set sail from New York on the S.S. Champlain. Father Hesburgh later recalled, "All my New York relatives, the Ahearns, the Nolans, all the Irish came down to see me off." He added, "We had a great trip across the Atlantic. I only got sick one day." He recalled roomy accommodations and "marvelous meals."

They landed in LeHavre and took a train to Paris, where they spent two days before traveling to LeMans, where the Congregation of Holy Cross was founded. They then went back to Paris, and then on to Rome. It was a busy several days, and by the time they arrived in Rome, they had been up for about twenty-four hours. After receiving an orientation from Father Georges Sauvage, the exhausted men were hoping for a good night's rest but were instructed to get up at 5:00 a.m. the next morning. Father Hesburgh recalled, "We would be getting up at 5 a.m. every morning, including Christmas, work or no work, holiday or no holiday."

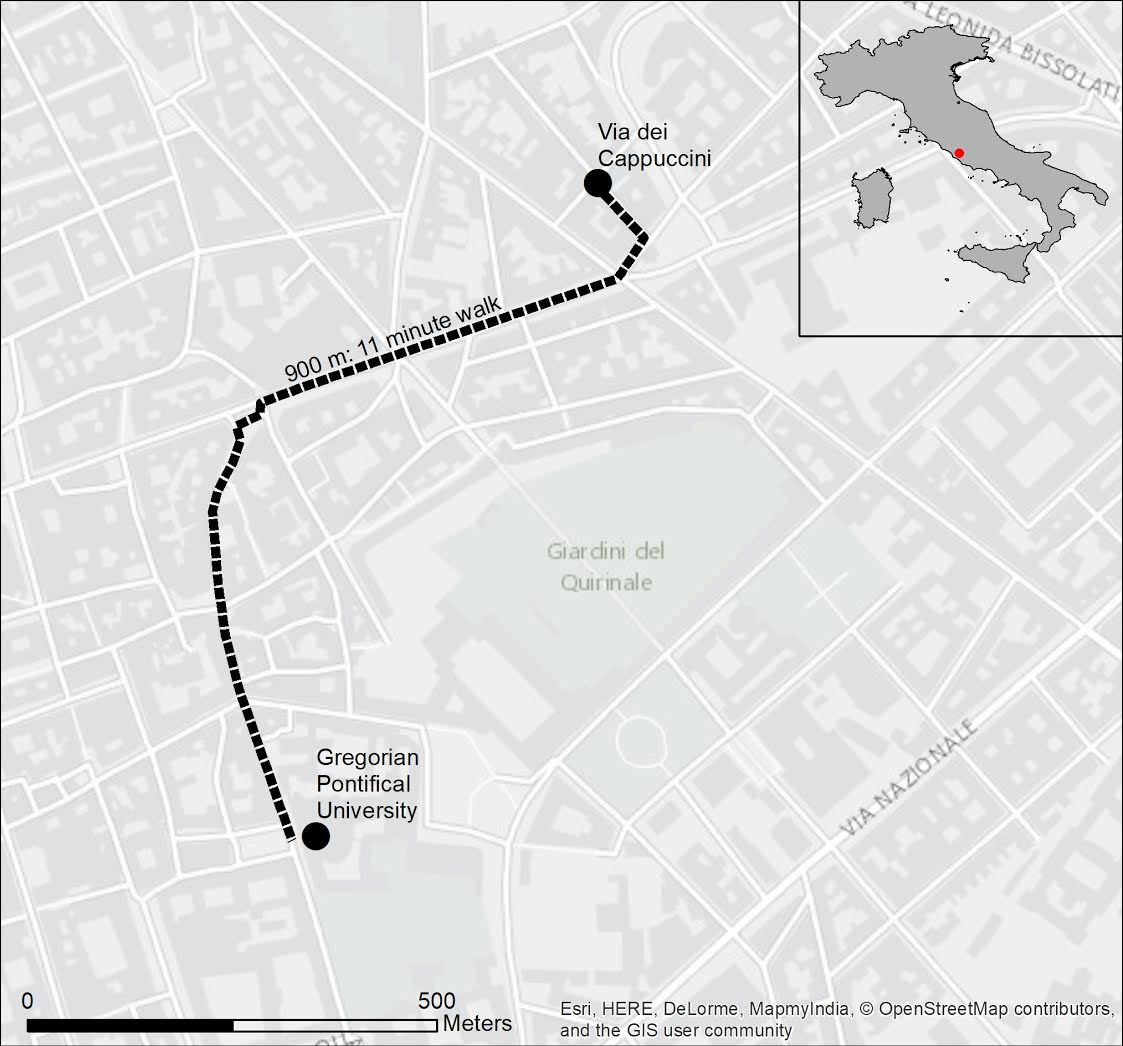

At their house, there were fourteen men: Father Sauvage, two other priests, a Holy Cross brother who was a house manager, and ten seminarians at various levels of formation, including the six from America. The house was large, and like many, had a marble floor, which was perfect in the warmer months, but terrible in the winter, especially given that there was no heat. There was one bath per floor to be shared by five men, and they were only allowed one hot bath per week. They were located centrally in Rome, so it was easy to get around. "It was a three-story house in a good section of Rome on the Via dei Cappuccini, a two-block street that comes down from the Capuchin church between Via Veneto and Via Sistina, two of Rome's most famous thoroughfares. We were only a block away from the Piazza Barberini and about a fifteen-minute walk to the Gregorian University, where we took our classes."

Source: Google Maps.

Father Hesburgh later described his education at the Gregorian as "truly international." "I was sitting in classes with students from every nation on earth-literally. There were forty-seven countries in the world at that time, and there was at least one student from each country at the University. Every single Catholic rite was represented."

All classes at the Gregorian were conducted in Latin. The men were required to converse in French at home, spoke Italian when out and about in the city, and learned Spanish from other students. Father Hesburgh recalled, "I made it a point never to speak English if I could avoid it." In his spare time, Ted studied French, Italian, and German vocabulary, learning ten new words in each language in one sitting. He added, "I grew to love languages and I have no doubt that the fluency I acquired in Rome helped me enormously in all the work I was to do the rest of my life."

They followed a fairly strict schedule from morning to night, but there was time every day for recreation. Every afternoon, the men would go out in pairs for a stroll around the city. In the evenings, the men had time for activities after supper. They could play ping pong or bridge, or just sit and talk (in French, of course). "We had no newspapers. We couldn't listen to the radio, and it was a fairly limited life as far as knowing what was going on in the world was concerned."

Over the summer following the first academic year in Rome, Father Hesburgh and the other seminarians spent two months in the Alps. Other than morning Mass and night prayers, they were largely on their own, and Father Hesburgh completed a long list of reading in German, French, and Italian. He credited the discipline he had learned at Most Holy Rosary and Rolling Prairie. He remembered his time there fondly. "It's hard to believe a more attractive or wonderful, quiet place to spend a summer than up on a mountainside."

Reflecting on his time at the Gregorian, Father Hesburgh said, "My education at the Gregorian, I have to confess, left a lot to be desired. The teaching was rigid and unimaginative and almost rote; the syllabus and instruction methods had not changed, I think, from the way things were done when they started the University in 1558." But he went on to say, "And yet, as rigid and old-fashioned as the Gregorian was, it provided me with good, intellectual discipline and a wonderful grounding in classical scholastic philosophy and in theology."

The summer following his second year in Rome was spent in the mountains in Italy. "We went to a place called Camaldoli ... in Central Italy and stayed at a big monastery there. That summer I did my eight-day retreat and took my final vows up in the hermitage up on top of the mountain."

The War Breaks Out

In the fall of 1939, Father Hesburgh was entering his third year in Rome, and the Second World War was beginning. Father Sauvage purchased a radio for the house; and from then on, they listened to the radio every night. Father Hesburgh recalled one night, they turned on the radio, and the Notre Dame Victory March was playing. "It was the beginning of the Army - Notre Dame game that was on international broadcast. Isn't that a curious thing?" Father Hesburgh remembered vividly the evening news "broadcast in French by the BBC and in English by Paris Mondial."

Father Hesburgh recalled:

Vaguely we realized that war in Europe was being talked about. Mussolini's residence was only a couple of blocks from the University on the Piazza Venezia, and his official quarters were right behind the Gregorian in the Quirinale. ... On one occasion, when Hitler was touring the historical sites of Rome in an open car, he passed down the Via Sistina no more than a hundred feet from the front door of our residence, Collegio di Santa Croce. Bill Shriner, a classmate, saw him from my window and called out, "Come over here and look out. Hitler is passing."

I shrugged it off indignantly as a matter of principle. "I wouldn't walk ten feet to see that bum," I replied, all my youthful idealism uppermost in my mind.

The following May of 1940, the American consul interrupted a morning class to announce that all Americans must leave the country in one week on the U.S.S. Manhattan. After having less than a week to study for his finals, Father Hesburgh completed the work for his undergraduate degree and earned a bachelor's degree in philosophy from the Gregorian University.

Arriving in New York City on the U.S.S. Manhattan, Ted's sister was on the pier to greet him, in the midst of what he later recalled as "pandemonium." He spent the next two weeks visiting his family in Syracuse before going onto Washington, D.C. to complete his studies.

Source: University of Notre Dame Archives.

While he was home, he wrote to his superior, Father Tom Steiner:

We never appreciated so much the freedom of America until we saw the results of the lack of liberty in Europe. It really is sickening to see the lives of so many people ruined, their hopes frustrated, their families disrupted, merely because a dictator thinks he owns them body and soul. We can't pray too much for war torn Europe, and heart broken Europeans. One aspiration I bring from Rome is to do whatever I can to keep America true to her ideals.