Caption

Caption

Source: University of Notre Dame Archives.

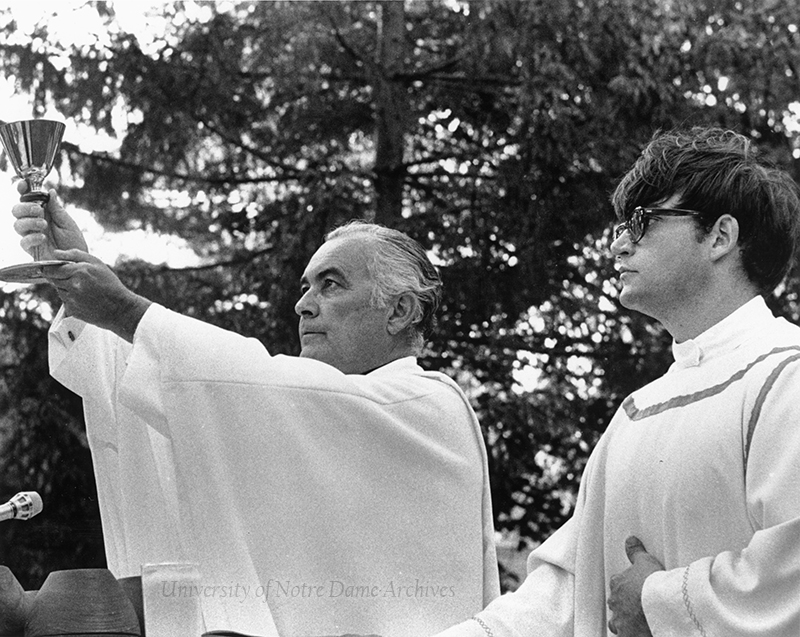

Ordination & Pastoral Work

Ordination

In June of 1940, following his sudden departure from Rome in advance of the Second World War, and after two weeks at home in Syracuse, Ted Hesburgh headed to Washington, D.C. He then spent the next three years studying at Holy Cross College. During this time, Father Hesburgh, and his friend, Charles Sheedy, got involved in writing booklets for men and women in the U.S. Armed Forces. Father Hesburgh recalled, "Together we cranked out a monthly news bulletin and a magazine for chaplains and a variety of publications as the need arose." They realized there was a need for a spiritual guide for servicemen. They found a French guide, Pour Mieux Servir (To Serve Better), and Father Hesburgh translated it into English. They titled it For God and Country and printed it as a pocket-sized book. Three-million copies were distributed.

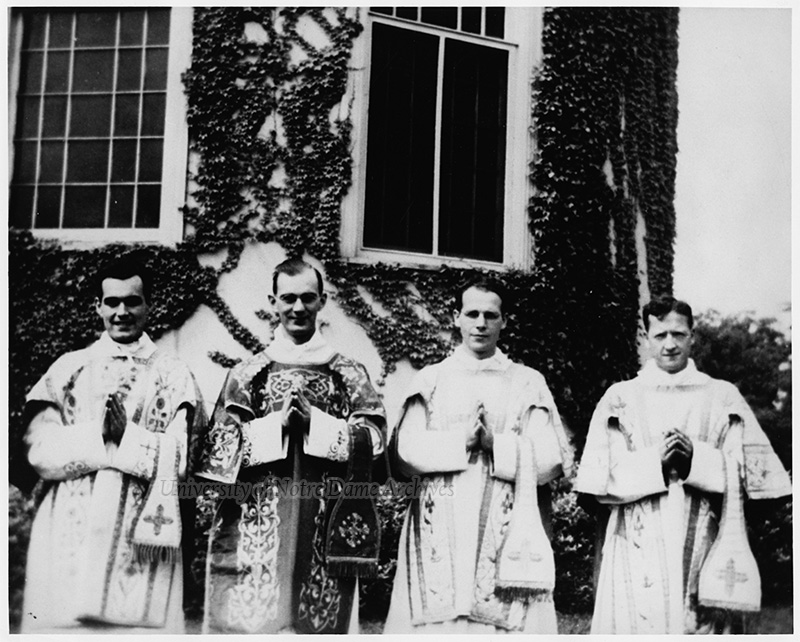

After three years at Holy Cross College (and one year of theology in Rome), Father Hesburgh earned his S.T.L., or licentiate of sacred theology. In June of 1943, he returned to Notre Dame for an eight-day retreat. On June 24, 1943, Theodore Martin Hesburgh was ordained a priest of the Roman Catholic Church at Sacred Heart at the University of Notre Dame, which he considered "one of the most beautiful Gothic churches in America."

Father Hesburgh later recalled seeing his family, along with those of his fifteen classmates, sitting in the front pews as he processed in. He remembered the Mass was celebrated in Latin by Bishop John Noll.

Source: University of Notre Dame Archives.

He later reflected:

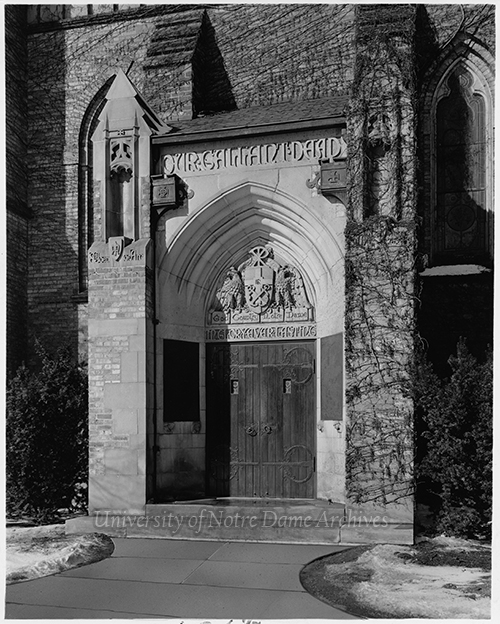

It was a solemn-joyous kind of a day, one of deep, abiding feelings for me as well as for my loving parents. I gave them and my sisters and brother my first priestly blessings. Nine years before, in September 1934, I had left home with a far-off dream to become a priest at Notre Dame, and when I walked out of Notre Dame's parish church, I, Theodore Martin Hesburgh, was what I had always wanted to be: a priest. Pausing, as had so many before me, at the sculptured east side door of Sacred Heart, a memorial to the Notre Dame men who had given their lives in World War I, I read the dedication above the door: God, Country, Notre Dame. I would dedicate my life to that trinity, too.

Source: University of Notre Dame Archives.

After the ordination and celebratory brunch at the campus dining hall, Father Hesburgh and his family drove to Norwalk, Ohio, where he said his first Mass at the Church of St. Paul. "St. Paul was always one of my favorite saints," he recalled in 1982. "We got home the next day, and I had two weeks at home, which were wonderful."

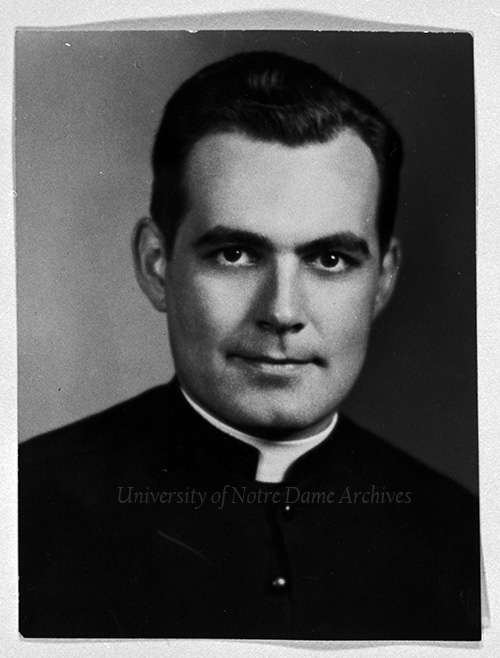

Work and Studies

Father Hesburgh remembered being "a young, sheltered, but very eager priest when I returned to Washington, and truly fortunate in coming in contact at the start with so many good priests who influenced my life by their advice and example." His first assignment as a priest was filling in for two weeks at St. Martin's Church in Washington, D.C., where he heard his first confession. "I considered myself lucky to have been assigned there." He remembered the Church's pastor, Father Bill, as "a warm, cheerful, giving man of enormous energy and goodwill."

Another one of Father Hesburgh's first duties was to conduct a three-day high school retreat on short notice. When the young priest questioned his own abilities to lead a retreat, the superior at Holy Cross College, Father Christopher O'Toole, was sure he could handle it. Father Hesburgh recalled Father O'Toole and his favorite response, "'Oh, you can do it,' and he left me to my own devices." Father Hesburgh learned to have more confidence in his abilities as a priest.

During the summers of 1943 and 1944, Father Ted had a more permanent assignment at St. Patrick's Church. Following his first summer at St. Patrick's, Father Hesburgh began his doctoral studies at the Catholic University of America.

Although his first year of doctoral work was demanding, Father Hesburgh was given the assignment of chaplain at the National Training School for Boys, which was a juvenile correctional institution run by the Department of Justice. He got to know the five-hundred boys there, where he attended meetings, held Saturday night confessions and Mass, and instruction on Sundays. He also worked at the Boys Club (now the Boys and Girls Club) and started a Newman Club at Howard University.

That academic year (1943-1944), Father Hesburgh also got involved with the Washington United Service Organization (USO), "a nonprofit organization that provides programs, services, and live entertainment to United States troops and their families." He was asked by a priest, Father Tom Dade, who hosted a radio show in Washington, D.C., to temporarily take over the USO club. Father Hesburgh became "a host and a friend to thousands upon thousands of servicemen and women who looked upon USO clubs as home away from home." They scheduled popular bands from around the country to play for free at the club. "It was not unusual to have two or three of these top name bands playing at the same time on different floors of the club for a thousand or fifteen hundred jitterbugging men and women in the uniforms of our Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marines. It was a sight to see." He added, "I became a super expert over night at dancing, but my job was mainly to circulate all night."

Father Hesburgh realized, after meeting thousands of women through the USO, that they were in need of a spiritual guide as much as men. So, based on letters he had written to his sister Betty, an officer in the WAVES (Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service), as well as conversations with the women he got to know in the service, he wrote Letters to Service Women and had almost half a million copies printed for the number of women in service.

In the publication, every letter begins, "Dear Mary, Bets, and Anne: . . ." and ends with "Love, as ever, from your brother, Father Ted." As a brother would, Father Hesburgh wrote that they were to avoid alcohol and watch out for men with "bad intentions." He also suggested that they go to Mass and Confession regularly, and pray daily. Largely, though, Father Hesburgh used the short, pocket-sized booklet as a means of encouragement. One letter reads:

Don't ever underestimate the tremendous importance of your way of life. . . . God had put us where we are for a purpose, but He leaves it up to us to find that purpose and to fulfill His Will in every task of every day. ... Nothing is insignificant in the plan of God.

One of the last pieces of advice in the letter reads: "Whatever you want to be and whatever you want to do in the future always remember that you are building the future now. ... Just stay close to Our Lord and His Blessed Mother and I know that the years will be fruitful."

Father Hesburgh later reflected, "Just a handful of us priests wrote these inspirational booklets on all manner of subjects, and overall, I would guess that between six and seven million copies of them were distributed throughout the armed forces. Judging from the incredible amount of mail they generated, I would think hundreds of thousands of lives were affected."

Source: University of Notre Dame Archives.

The Dissertation

During his second year of doctoral studies, Father Hesburgh was quite busy. Besides a heavier than usual course load, he also had to write his five-hundred-page dissertation to submit by March 1 in order to graduate the following spring. When he wasn't in class, or acting as chaplain, he was working on his dissertation from 7 a.m. to 12 a.m., every day except Christmas. The title of his dissertation was The Relation of the Sacramental Characters of Baptism and Confirmation to the Lay Apostolate. He credits his friend Jim Doll, a Holy Cross seminarian, for typing ninety pages of footnotes (which included eight languages), and Jim Norris, who directed the National Council of Catholic Servicemen, for giving Father Hesburgh five of his best typists to type the necessary five copies of five-hundred pages of text. He recalled the stressful day his thesis was due:

The day the dissertation was due, the five young women were still typing and I was beginning to get apprehensive. The head of the theology department, a monsignor named Joseph Fenton, was known as a stickler on rules. A deadline was a deadline. Mine was five o'clock. No exceptions.

The dissertation was done with ten minutes to spare, and a kind-hearted secretary bent the rules and kept the office open to accept it twenty minutes late.

Father Hesburgh then successfully defended his dissertation and had it published with the new title, Theology of Catholic Action. After graduation, he wasted no time in contacting his superior, Father Steiner, and reminded him of his desire to be a Navy chaplain. One of his friends promised him a place in the class of chaplains at the College of William and Mary (which would lead to a chaplaincy on the Pacific) if he were given permission by his superior. He waited two weeks for a reply in the mail.

The letter finally came, and it was not what Father Hesburgh was hoping to hear. Father Steiner said he was to go home for a week, then return to Notre Dame to teach. Thousands of officer candidates were being sent by the Navy to Notre Dame for training, and he was needed on the faculty. Father Hesburgh later said, "It was as if the Lord were saying to me, 'Your planning is terrible. Leave it up to Me.'"