President of Notre Dame

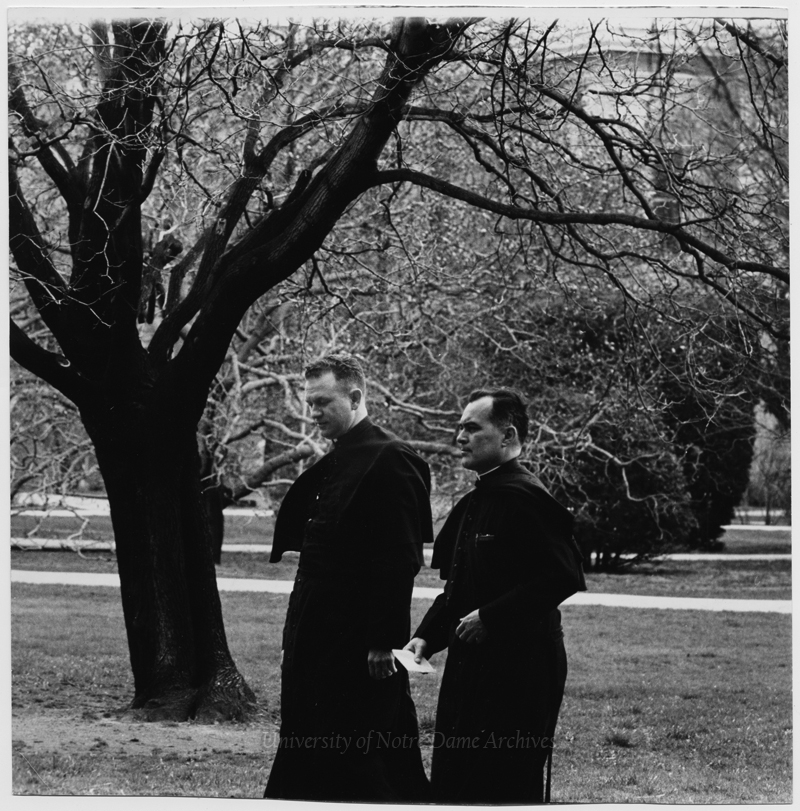

In 1949, Father John J. Cavanaugh chose Father Hesburgh to be his executive vice president and would spend the next three years mentoring the young priest and preparing him to take over the presidency. In 1952, at the age of 35, Father Hesburgh was named president of the University of Notre Dame.

Father Hesburgh was glad that Father Cavanaugh was nearby and later reflected in his autobiography, God, Country, Notre Dame, "I regularly turned to Cavanaugh for advice and he shared his wisdom and counsel freely on a wide range of university matters. He knew so much more than I did. But he never offered advice unless asked. In many ways he was like a father to me." One piece of advice that Father Cavanaugh shared with Father Hesburgh was to hire the best people he could find and delegate responsibility to them.

As discussed in Teaching, Research, and Faculty Growth, Father Hesburgh was involved in improving all areas of the University. One of the first areas that needed improvement was finances. As executive vice president, Father Hesburgh had discovered the University didn't have any sort of budget, so it was clear the system needed to change. Father Cavanaugh had chosen Father Ned Joyce, C.S.C., a certified public accountant, as his financial vice president to begin to reorganize this area.

Source: University of Notre Dame Archives.

As Father Hesburgh described his friend and colleague in God, Country, Notre Dame, "He was good at everything I wasn't, particularly financial matters. While I focused on academics, Ned reigned over finances, buildings and grounds, university relations, athletics, and everything else." Delegating responsibility of the day-to-day operations of Notre Dame meant that he would have time to tackle creating what he envisioned as the great Catholic university. According to biographer Michael O'Brien, "In just a few years at Notre Dame, Fr. Ted had made a remarkable impression. 'Hesburgh was like a breath of fresh air around here,' said a colleague. 'He was incredibly charming and energetic. He landed on both feet and started running.'"

"'Certainly, I pull the strings,' he modestly told an interviewer after he assumed the presidency, 'but it's the strings I pull who do the work.'"

Fundraising

While executive vice president, Father Hesburgh had quickly learned how important fundraising was to support the University and its goals. Father Cavanaugh introduced Father Hesburgh to the "world of benefactor relations." According to Father Hesburgh, his mentor was "the father and pioneer of modern, professional fund-raising at Notre Dame. He propelled us into a new age. Academic excellence was his goal and he knew it would cost money."

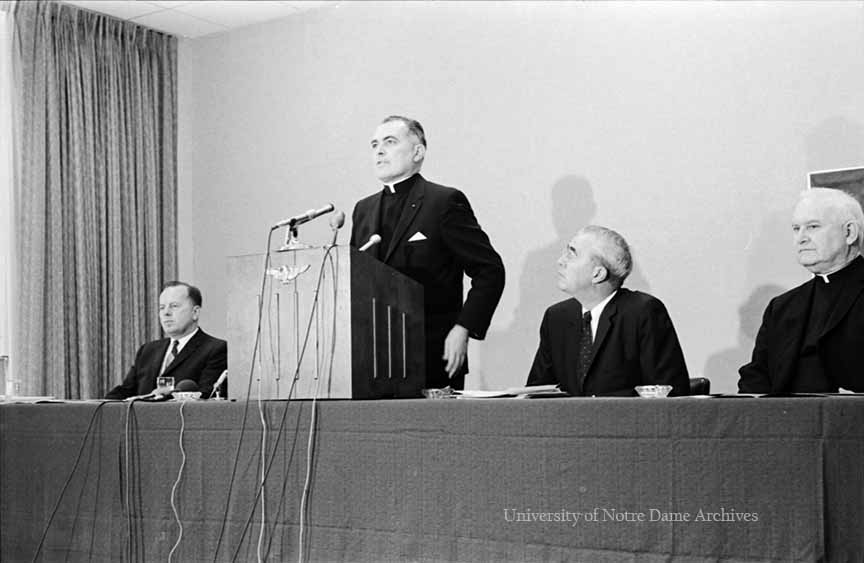

A grant from the Ford Foundation played a large part in the University's rapid growth. In September 1960, the Ford Foundation chose Notre Dame, along with four other private universities (Stanford, Johns Hopkins, University of Denver, and Vanderbilt University) to receive a conditional grant of $6 million. If Notre Dame could raise $12 million, they would receive the full grant of $6 million from the foundation. According to a Scholastic article, the grants were given "to assist institutions in different regions of the country to reach and sustain a wholly new level of academic excellence, administrative effectiveness and financial support." Notre Dame received the full grant, and three years later raised $16 million and was given another $6 million from the Ford Foundation.

In 1967, Father Hesburgh launched the largest fundraising campaign in Notre Dame history, the Summa Program, aimed to raise $55 million over five years to cover the cost of significant growth in faculty, research, and graduate programs. Twenty million dollars would allow the University to provide 40 endowed professorships.

Fundraising provided the University the means to physically improve the campus. In just the first six years, Father Hesburgh was responsible for twelve new buildings. By the end of his tenure as president, the campus had changed dramatically. There were forty buildings built, and nearly all of the old structures on campus had been renovated.

Television

Building on the success of the student-run radio station, which was broadcast on the Notre Dame and Saint Mary's campuses since the 1930s, Father Hesburgh and Father Joyce decided to join "the highly competitive field" of television, as a Scholastic article described it. According to Michael O'Brien, Father Hesburgh was "concerned with the effect of television on education and served on several committees on educational television." So, when someone proposed building a station at Notre Dame, Father Hesburgh jumped on the idea. He thought it would be great for students in journalism.

The station, WNDU-TV, was built on the site of the old Vetville Recreation Hall. It was run by professionals, but Notre Dame students were employed in the studio and trained in a variety of positions. The station, which was owned by the Michiana Television Corporation, under the University of Notre Dame, first went on air on July 15, 1955 and was dedicated on September 30 that year. Though originally created as an educational station, it would later become commercial and an NBC affiliate.

Source: University of Notre Dame Archives.

Lay Governance

One of the most controversial decisions Father Hesburgh made during his presidency was the transfer of University governance to lay control. Father Hesburgh saw that the Second Vatican Council was encouraging the laity to take on more active roles within the Church. In his autobiography he wrote that "Vatican II had said that laypeople should be given responsibility in Catholic affairs commensurate with their dedication, their competence, and their intelligence."

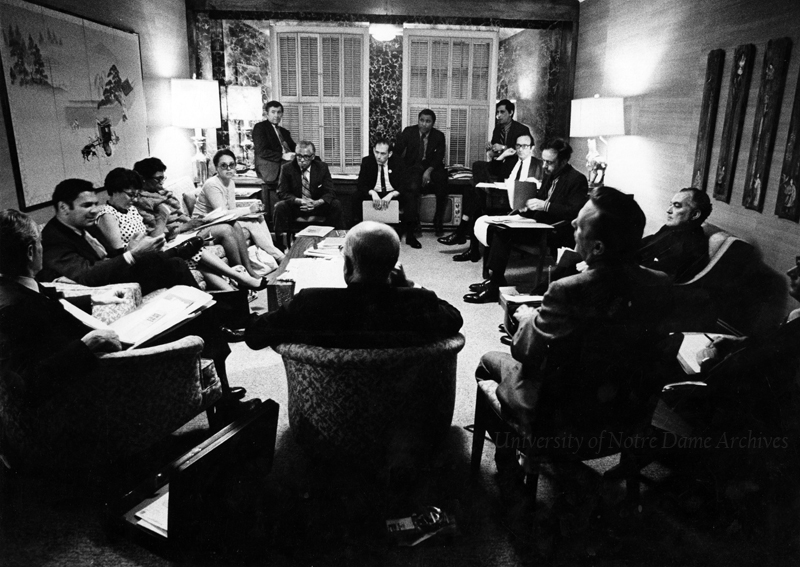

In the summer of 1965, Father Hesburgh gathered the father general and father provincial of Holy Cross, the University vice presidents, and several trustees at Land O'Lakes, Wisconsin, the quiet country retreat that the University owned, to discuss the changing of governance. It was clear to those gathered that the change was necessary for the survival and flourishing of the University. In January of 1967, a special council was held to officially decide to move forward with the decision, and they then sought approval from the Holy See. Once that was granted, they worked to set up an entirely new system. Father Hesburgh recalled in God, Country, Notre Dame,

The work was intricate and delicate because every decision was crucial, not only legally but culturally. We all wanted Notre Dame to continue as it had before, as a premier Catholic university, and also to grow stronger academically and economically.

The University would be run by a lay board of fellows, which would include six Holy Cross priests and six laypeople. They would be part of the larger board of trustees. "Their main function was to maintain the Catholicity of the university and its integrity of purpose. One statute, for example, states that the president of the university always must be a priest of the Indiana Province of Holy Cross."

Source: University of Notre Dame Archives.

Coeducation

Established in 1842, the University of Notre Dame, as most other colleges and universities in the United States, was an all-male institution. In 1917, during the University's seventy-fifth jubilee, the first two women received master's degrees at commencement, both Holy Cross sisters from Saint Mary's College. The following year, the University would officially open a summer school, which offered undergraduate and graduate courses to both men and women, geared toward teachers. Over the next fifty years, thousands of women would receive degrees from Notre Dame, but women were not yet truly part of the student body.

In 1965, Father Hesburgh sought to make a change and started a co-exchange program with Saint Mary's College. This program allowed students on both campuses to take courses at the other campus. After a failed merger with Saint Mary's a few years later, Notre Dame made the decision to become coeducational in 1972. The change was gradual, but Notre Dame slowly admitted more and more women.

By the time Father Hesburgh retired, enrollment of women was just under forty percent of the total, and including the women at Saint Mary's, as Father Hesburgh did, the women had an equal presence between the two campuses.

Center for Civil and Human Rights

In 1957, Father Hesburgh was selected by President Dwight D. Eisenhower as one of the six members of the newly created U.S. Commission on Civil Rights. Father Hesburgh spent fifteen years bringing to light the many injustices in the country and helped spur real change. When Father Hesburgh was chairman of the commission and found the federal government to be lacking in its enforcement of civil rights, he was forced by President Richard Nixon to resign. Father Hesburgh was passionate about the cause and found a way to continue his work, and felt there was no better place for this than Notre Dame.

One year after he left his post as commissioner and chairman, Father Hesburgh founded the Center for Civil Rights at Notre Dame "as a place of learning to advance justice and dignity for all people." It would be a place for educating students about injustices around the country and later injustices throughout the world. According to its website, "by 1976 the Center had begun to fully embrace the field of human rights, and under the guidance of the Center's second director, Donald Kommers, new areas of research were being tapped." And it would soon become the Center for Civil and Human Rights, as was Father Hesburgh's vision, "to defend human dignity by promoting democracy, peace, and justice across the globe." The center began to educate and train human rights lawyers from around the world with the mission of:

Raising awareness of particular forms of oppression among activists, officials, scholars, and students in order that they may promote human rights more effectively. These commitments emanate from the Catholic tradition of justice found at the heart of the University of Notre Dame.

Source: University of Notre Dame Archives.

Center for Social Concerns

Father Hesburgh would often encourage students to reach out in service of others, what he saw as a key component to the Christian life. Whether it was serving in some capacity on campus, in the local community, or halfway around the world, volunteer efforts thrived during Father Hesburgh's tenure as president. There were several services on campus that sought to serve the community. Two of the main centers were the Notre Dame Office of Volunteer Services (under the Office of Student Activities) and the Center for Experiential Learning (under the Institute for Pastoral and Social Ministry).

In the late 1970s, a new center was founded to merge the two initiatives into one-the Center for Social Concerns. Its mission would be "to advance the common good through community-engaged teaching and research grounded in the Catholic social tradition." And its purpose continues to align with Father Hesburgh's vision of a Catholic university dedicated to service. According to its website,

Through pedagogies of engagement, research addressing injustice and inequality, and partnerships with communities near and far, we seek to advance the common good in all we do. We seek to inspire our students as they become agents of social justice, to collaborate with our academic colleagues in teaching and research responsive to the signs of the times, and to accompany our community partners as they discern and address pressing challenges.

Source: University of Notre Dame Archives.

Father Hesburgh accomplished a great deal as president of the University of Notre Dame. This summary barely scratches the surface of what he had accomplished at Notre Dame, but it highlights some of the initiatives for which he was most proud. And Father Hesburgh would be the first to mention all of the people who helped him along the way. He firmly believed in community, and the good that can come from a united front. But he also sought to encourage individuals to do great things with their lives. Father Hesburgh hoped to inspire others to follow the Holy Spirit and use their gifts for the greater good. Toward the end his autobiography, he reflected, "One person can make a difference. And no one knows what he or she is capable of until he or she tries."