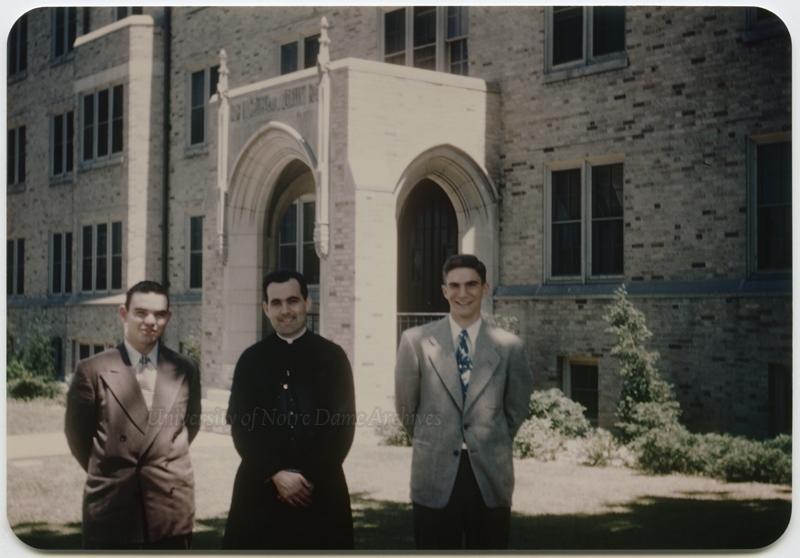

Caption

Caption

Source: University of Notre Dame Archives.

Rise to the Presidency

Administration

While Father Hesburgh was an instructor in the Religion Department, rector of the veterans at Notre Dame at Badin Hall, and chaplain of Vetville, the community of married veterans on campus, Notre Dame President Father John Cavanaugh approached him about becoming dean of the College of Arts and Letters. Father Hesburgh recalled in his autobiography, "I felt an aversion to all the paperwork that goes with being a dean; I didn't want to be an administrator of any kind, and I told Cavanaugh that. Kindly, he did not persist, and that was the end of it, or so I thought."

In the summer of 1948, life began to change quickly for Father Hesburgh. Father Cavanaugh approached him about going into administration, but Father Hesburgh was reticent. Father Hesburgh admitted to him, "Isn't it curious that by doing what I was told to do, rather than what I thought I wanted, I've managed to have a happy life."

Farley Hall

After having been rector of the veterans of Badin Hall, who were all a bit older and more mature, it was a new experience for Father Hesburgh to be in charge of the freshmen of Farley Hall. He remembered the "explosive mixture of 330 seventeen- and eighteen-year-old freshmen stuffed two and three to a room, away from home for the first time, innocent and ignorant of caring for themselves." He was working on turning his class notes into a book and found the only time he had to do so was between the hours of midnight and two a.m.. Then he would be up again at seven a.m. for daily Mass in the hall chapel.

Executive Vice President

At the end of the academic year, in the spring of 1949, Father Hesburgh ran into Father Cavanaugh on the way to the Crypt at Sacred Heart Church to receive their priestly "obediences," or assignments, for the next year. As they approached the chapel, Father Cavanaugh said to Father Hesburgh, "By the way, Ted, you're going to be made vice president today." He replied, "Oh, come on, Father John, you've stuck me with a department and a hall, but vice president? God in Heaven, I don't want to be a vice president." Thinking Father Cavanaugh was joking, Father Hesburgh was shocked when his name was called. He was one of the youngest priests there and would be executive vice president, in charge of priests who were older and more experienced.

According to historian Michael O'Brien in Hesburgh, A Biography, "In the late 1940s Notre Dame had virtually no scholarship funds or endowment, no liberal arts building, no science building, an inadequate library, and a shortage of dormitories." He added, "Salaries were low and the lay faculty lived in genteel poverty. With most power vested in the president, the university was authoritarian in structure." Father Cavanaugh was overburdened by the amount of work that lay on his shoulders, and sought to create a structure to better disburse work. Notre Dame was lucky to have an intellectual and former businessman as president. According to O'Brien, "In 1947 Cavanaugh established the Notre Dame Foundation, the first ongoing fund-raising program in the university's history. He recruited faculty from Europe, and these scholars helped enrich and professionalize the Notre Dame faculty."

Source: University of Notre Dame Archives.

Reorganization

Father Cavanaugh was in the process of reorganizing the administration of Notre Dame, and sought out Father Hesburgh's help. Father Hesburgh recalled, "My first job was to write up an administrative procedure and a job description for each vice president's area of responsibility, including my own." He would address academics, student affairs, finance, and public relations. Father Cavanaugh told Father Hesburgh, "'I want articles of administration, lines of authority, organizational charts, and areas of responsibility, the whole works.'" Father Hesburgh addressed problems he saw in various departments across the University. According to O'Brien, Father Hesburgh discovered the University had no budget, and stated in a memo to Father Cavanaugh that it was a miracle they had survived thus far without one. "Maybe we should begin the budget meetings with a prayer to the Holy Spirit and end them with a Hail Mary."

When Father Hesburgh was tasked with reorganizing athletics, he worked with football coach, Frank Leahy, "who happened to be the most famous, most talented football coach in the country." Father Hesburgh installed an athletic director who reported to the executive vice president, cut back spending, limited the number of complimentary football tickets that were disbursed, and enforced strict compliance of the Big Ten Conference rule with regard to the number of players to travel to away games.

Source: University of Notre Dame Archives.

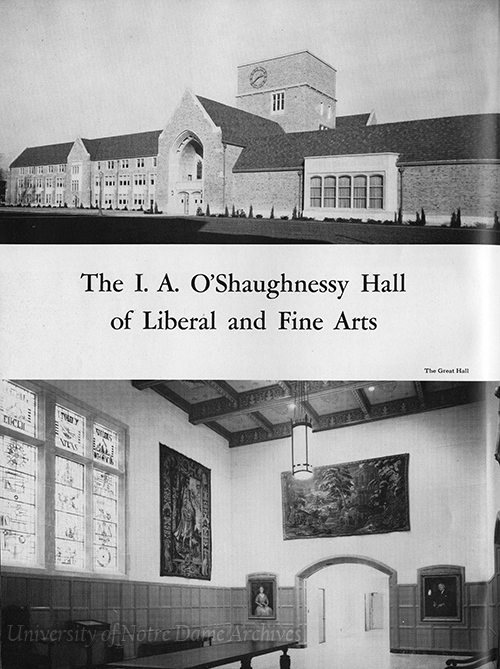

Buildings

In addition to his various other duties, Father Hesburgh was put in charge of five construction projects on campus: Fisher Hall, Nieuwland Science Hall, O'Shaughnessy Hall, the Morris Inn, and the power plant. He was to oversee them from start to finish. Father Hesburgh recalled in his autobiography, "My education in the complex world of architecture, design, construction, and building materials was swift and awesome. I learned because I had to." The style of architecture at Notre Dame was largely Collegiate Gothic, and for the most part, buildings were designed prior to any consideration for function. Father Hesburgh revamped the way buildings were erected at Notre Dame and placed function over form. He would write up detailed instructions, let architectural firms bid for design of a particular building, and then Notre Dame would choose the best design at the best cost. Rather than using the same construction company as in the past, Father Hesburgh would take sealed bids on construction. In the end, he saved the University a great deal of money.

Source: University of Notre Dame Archives.

It was a busy three years and an unexpected turn in Father Hesburgh's life. But he was clearly the right man for the job. Father Hesburgh reflected on his time as executive vice president:

During those three years, Cavanaugh assigned to me a multiplicity of overlapping projects, both large and small, more than I thought I could handle, and I sometimes wondered about his seemingly unbounded faith in me. And yet, somehow, I rose to the occasion; a job had to be done and one did it, and learned something on the way.

President of Notre Dame

Through the course of those three years, Father Cavanaugh seemed to be gradually giving more and more responsibilities to Father Hesburgh. He spent a summer away in Rome at a meeting of the Holy Cross Congregation, then his health required him to recover in Florida for a couple months in early 1952. There was no question who Father Cavanaugh's successor would be when he came to the end of his six-year term that June. Prior to the handing out of the yearly obediences, Father Hesburgh was asked who he wanted as vice president. He recalled in his autobiography, "Nevertheless, my stomach flipped over when I heard him announce, 'Ted Hesburgh, president.'"

After obediences in the chapel, Father Cavanaugh simply handed Father Hesburgh the key to his office, saying, "'I promised to give a talk tonight to the Christian Family Movement over at Veterans Hall. Now that you're president, you have to do it. Good luck. I'm off to New York.'"

Source: University of Notre Dame Archives.