Caption

Caption

Source: University of Notre Dame Archives.

Coeducation: The Beginning

I grew up with three sisters. . . . They were wonderful ladies. My life is a lot richer because I was not just formed by my mother and father but by them.

- Father Hesburgh

The First Women

When the University of Notre Dame was founded by the Congregation of Holy Cross in 1842, it was an all-male institution. Though it was still officially considered an all-men's school 110 years later when Father Hesburgh became president, thousands of women, largely religious sisters, had earned degrees from Notre Dame.

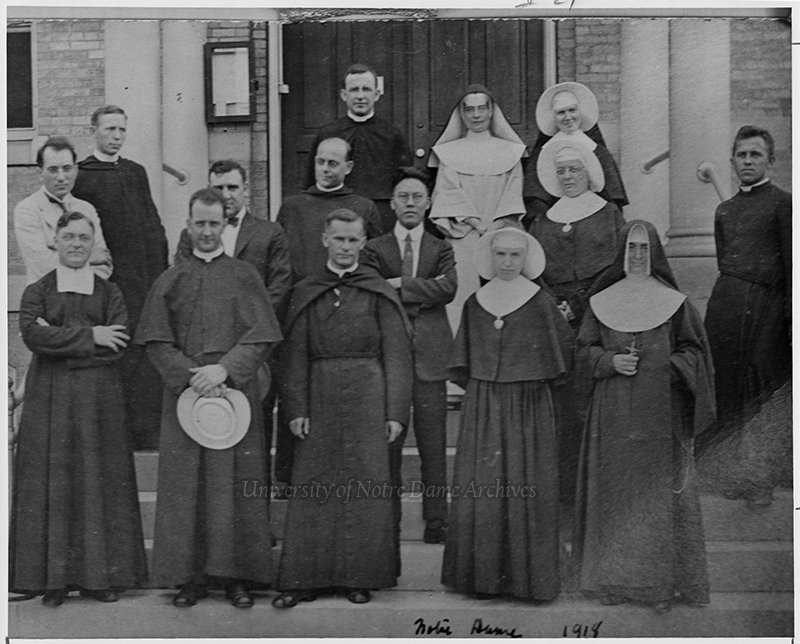

In 1917, the first two women graduated with masters degrees, Sister Mary Frances Jerome (MA, with the thesis The Position of Woman in Greek Literature) and Sister Mary Lucretia (MS, with the thesis Domestic Chemistry). A year later, Notre Dame officially opened the Summer School Program, which included both undergraduate and graduate courses, and admitted both men and women. Women came from all over the country to study at Notre Dame, but since most could only attend courses during the summer months, it often took them several years to earn their degrees.

Source: University of Notre Dame Archives.

In 1922, five women received their bachelor's degrees, including four religious sisters and one laywoman. They were the first women to receive undergraduate degrees in the school's history. They were: Sister Mary Aloysi Kiener (Sisters of Notre Dame, Cleveland, Ohio), Sister Margaret Mary (Sisters of Charity of St. Augustine, Lakewood, Ohio), Sister Mary Josephine (Ursuline Sisters of Brown County, Ohio), Sister Mary Veronique (Sisters of the Holy Cross, Saint Mary's, Notre Dame, Indiana), and Antoinette Semortier (South Bend, Indiana).

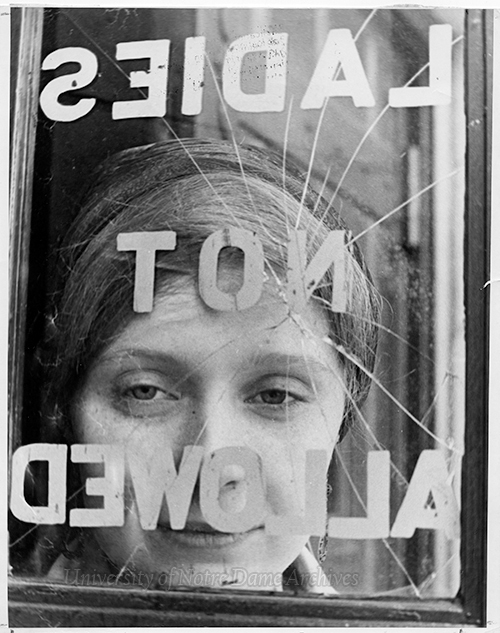

Women would continue to earn degrees at Notre Dame, but were largely overlooked because they were only present on campus a few months out of every year. In 1932, the graduate school officially began admitting women. If a woman lived in town, she could attend school during the academic year, but if not (as was the case for most), she was limited to the summer sessions.

A Home on Campus

Source: University of Notre Dame Archives.

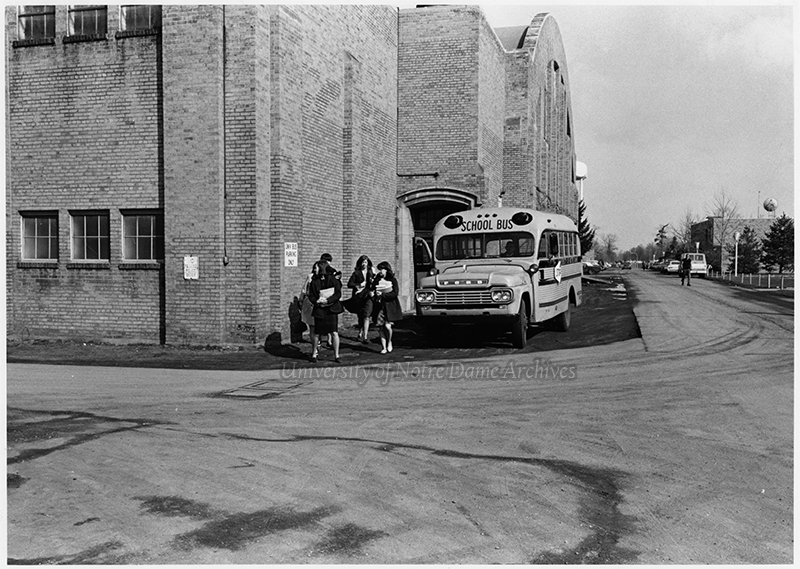

In 1965, a new hall was dedicated at Notre Dame: the first women's dormitory. The Frank J. Lewis Foundation donated $1 million for the construction of the dormitory on campus, specifically for religious sisters, which allowed women to attain their degrees much more quickly.

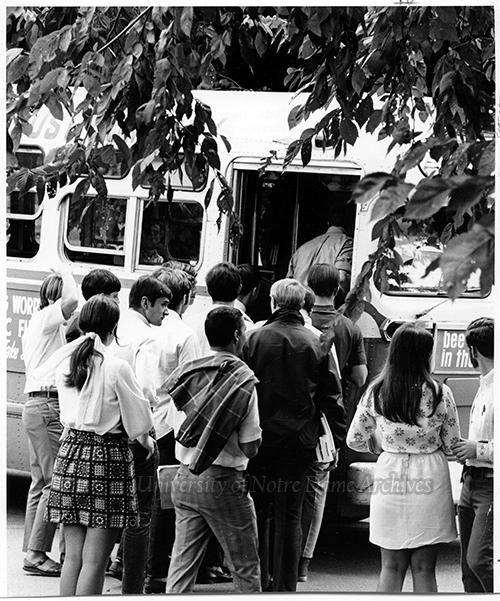

The same year Lewis Hall was built, Notre Dame began a co-exchange program with Saint Mary's College, a natural first step toward full coeducation. Though Father Hesburgh was supportive of coeducation, and Saint Mary's students had been quietly sitting in on classes at Notre Dame for years, many administrators and alumni were adamantly opposed to the idea of coeducation.

Source: University of Notre Dame Archives.

In an interview, Father Hesburgh recalled:

It struck me that if we are in the education business for higher education in the Catholic Church in America, we can't say we are doing this and ignore half of the American Catholic population. So, I began to make a few noises. It was obvious this was not going to be an easy thing to do.

So he, and his supporters, took baby steps initially. Father Hesburgh mentioned in his autobiography, "I resolved to do whatever I could to improve the relationship between the two schools. I supported anything that would give the Saint Mary's women a reason to visit our campus-dances, plays, concerts, and so forth." In 1965, the co-exchange program between Notre Dame and Saint Mary's College officially began. Women from Saint Mary's and men from Notre Dame, could enroll in undergraduate courses at the other's campus that were not offered at their respective school. Very few took advantage, but it was a start.

Source: University of Notre Dame Archives.

In the 1960s, Saint Mary's women were admitted to staff positions at Notre Dame student publications, and became more involved in social life at Notre Dame. In the late 1960s, Father Hesburgh opened the doors to women in the Law School. In 1967 the Notre Dame and Saint Mary's theaters combined. All signs pointed to an eventual merging of the schools, and a questionnaire went out to the students and staff of both schools concerning future cooperation.

During this time, the University of Notre Dame was also considering a possible merger with Barat College in Lake Forest, Illinois. Barat College nearly made the move, but a potential sale of their Illinois campus fell through, and the move to South Bend would have been prohibitive. Two other schools that were also being considered were Rosary College (now Dominican University), and Mundelein College, both in Chicago. Rosary College decided to become coeducational on its own, and a relationship with Mundelein College never materialized. (The college was later absorbed by Loyola University of Chicago.)

A Merger

In 1969, two academic consultants, Rosemary Park (former president of Barnard College) and Lewis B. Mayhew (Stanford University), studied Notre Dame and Saint Mary's and the potential for future collaboration. Their report (the Park-Mayhew Report) in January 1971, suggested that the two schools work in cooperation but not merge entirely. The compromise for the time being would include a merging of most departments and offices, and would allow for students at Saint Mary's to pursue majors at Notre Dame, and students at Notre Dame to pursue majors at Saint Mary's.

Two months after the Park-Mayhew Report was made public, the University issued a press release stating:

A unification of the University of Notre Dame and neighboring Saint Mary's College has been recommended by the executive committees of their boards of trustees. The unification will begin immediately and be completed not later than the academic year 1974-75.

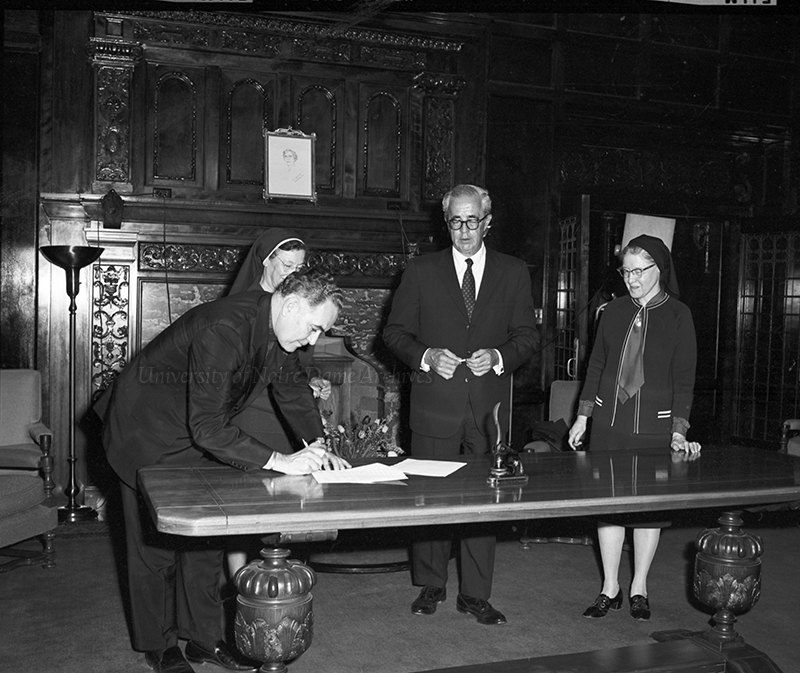

Source: University of Notre Dame Archives.

In May, the merger was formally announced, and the two schools moved toward unification, to be completed by September 1. There would be no housing changes, but departments of the two schools would merge, student governments would combine, and students could register in any degree program at either school. Father Hesburgh explained,

We would have one faculty, one extended campus. Women would continue to be admitted to Saint Mary's or through Saint Mary's, but they would receive Notre Dame degrees with a notation that the degree had been granted at Saint Mary's College. There would be a common board of trustees, a common budget, a common everything. We would do our best to integrate the two campuses.

As the fall semester began, Notre Dame and Saint Mary's College seemed to be busy organizing a merger. In November, it was becoming clear that the merger was not going as smoothly as hoped. Father Hesburgh wrote,

The main difficulty was tied up with the problem of identity. They did not want to lose their identity. It was very much their own. You could not blame them. For more than a century, talented and heroic Holy Cross women had devoted their lives to achieving identity.

On Tuesday, November 30, 1971, nearly the end of the fall semester, Notre Dame issued a press release that in part read: "It is not possible to accomplish complete unification at this time." That announcement was followed by the decision to go coed with or without Saint Mary's College.