Caption

Caption

Source: University of Notre Dame Archives.

Protest in the 1960s

The high idealism, vigor, and youthful hopes that marked the inauguration of John F. Kennedy in 1961 ended in disillusion, anger, and finally violence when the 1960s came to an end. College students, our traditional hope for the future, questioned the established values upon which they were raised, and then at least some of them revolted against everything that represented adult authority. Proclaiming their distrust of everyone over thirty, they fled parental authority, wore ragged clothing, used foul language, turned to mind-altering drugs, disdained the work ethic, family and marriage, and more-all to find a new meaning and a new way to live their lives. ... When they wanted to voice their protests, they struck out, of course, at what was nearest to them: the colleges and universities from Berkeley in San Francisco to Columbia in New York City. - Father Hesburgh, God, Country, Notre Dame

Source: University of Notre Dame Archives.

The 1960s were tumultuous years in America. A large part of the country wanted a true democratic society, firmly committed to civil rights for all. The young Baptist minister, Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., was at the forefront of peaceful protests. John F. Kennedy was inaugurated president of the United States in 1961, promising the nation a new, peaceful, and hopeful future for all. But shortly before reaching three years in office, Kennedy was assassinated, and the shocked nation's general discontent and unrest became more and more widespread.

When Lyndon B. Johnson took office after Kennedy's death, he promised to continue the late president's work and made some remarkable strides in civil rights. But he also forged ahead in Vietnam, drastically increasing the number of troops and therefore losing the support of many people. The Americans were trying to defend the Vietnamese from a growing communist regime, but were increasingly on the offensive. President Johnson heavily increased the deployment of Americans for ground combat. Johnson also initiated a series of bombings that made it clear to the American public that the country was no longer on the defensive. Young men and women, especially those enrolled in colleges and universities across the country, began expressing their general disillusionment. And protests ranged from peaceful to violent.

Biographer Michael O'Brien wrote in Hesburgh: A Biography,

The first major U.S. campus protest had occurred at the University of California at Berkeley in the fall of 1964, when a number of campus groups united under the Free Speech Movement. Mass rallies, the takeover of university buildings, and police raids against demonstrators highlighted the student revolt. The unrest at Berkeley became the scenario that repeated itself on hundreds of campuses during the rest of the 1960s.

In April 1968, Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., was assassinated in Tennessee. Race riots erupted across the country. Two months later, Senator Robert F. Kennedy, the popular brother of the late John F. Kennedy, supporter of King, and candidate for the fall presidential election, was shot to death in California.

Richard Nixon was elected president in the fall of 1968. He sought to bring peace in Vietnam and withdraw American troops, but under him, the first draft lottery since World War II was instituted, and more and more young men were sent to fight a losing war. The result was horrific. "More than 3 million people (including 58,000 Americans) were killed in the Vietnam War; more than half were Vietnamese civilians."

Source: University of Notre Dame Archives.

In November of 1968, a large demonstration took place at Notre Dame-the largest in the University's history. Three hundred students lined up in the administration building and took part in a "sit in" to protest recruiters from Dow Chemical and the Central Intelligence Agency.

Father Hesburgh wrote a letter to faculty and students on November 25, 1968. Essentially, he asked the campus community to help determine a peaceful and productive way forward. And students appreciated the open dialogue he promoted through the letter.

Around the country it was apparent that the scene on college campuses was not improving. Things were not getting better, but simply escalating. Father Hesburgh knew he had to act. He recalled, "The fundamental question was where to draw the line." He came up with a stance somewhere in the middle of supporting protest and free speech, and protecting the day-to-day operations of the University. On February 17, 1969, Father Hesburgh garnered support from the colleges within the University and composed an eight-page letter to the students and campus community. In part, he wrote the following:

Youth especially has much to offer-idealism, generosity, dedication, and service. The last thing a shaken society needs is more shaking. The last thing a noisy, turbulent, and disintegrating community needs is more noise, turbulence, and disintegration. ... Compassion has a quiet way of service. ...

The university cannot cure all our ills today, but it can make a valiant beginning by bringing all its intellectual and moral powers to bear upon them: all the idealism and generosity of its own people, all the wisdom and intelligence of its oldsters, all the expertise and competence of those who are in their middle years. But it must do all this as a university does, within its proper style and capability, no longer an ivory tower, but not the Red Cross, either.

... The university could not continue to exist as an open society dedicated to the discussion of all issues of importance if protests were of such a nature that the normal operations of the university were in any way impeded, or if the rights of any member of this community were abrogated, peacefully or nonpeacefully.

Father Hesburgh then laid out his "15-minute" rule, which would give any disruptive demonstrator 15-minutes to "cease and desist." They would be given a chance to do so at that time, but after five more minutes, would be suspended. If they chose to persist, they would be expelled from Notre Dame.

We only insist on the rights of all, minority and majority, the climate of civility and rationality, and a preponderant moral abhorrence of violence on inhumane forms of persuasion that violate our style of life and the nature of the university.

He concluded the letter with a warning.

If I read the signs of the times correctly, this may well lead to a suppression of the liberty and autonomy that are the lifeblood of a university community. It may well lead to a rebirth of fascism, unless we ourselves are ready to take a stand for what is right for us. History is not consoling in this regard. We rule ourselves or others rule us, in a way that destroys the university as we have known and loved it.

Word of the letter spread like wildfire. According to biographer Michael O'Brien, "about 250 newspapers stormed into print, almost all of them praising his tough stand."

Not all took the letter seriously. According to O'Brien, "Senator Eugene McCarthy, who spoke at Notre Dame, was asked about Fr. Ted's hard-line statement on student disorders. With a mischievous smile, McCarthy opined that it was like warning an all-girl band not to chew tobacco." It was certainly true that there seemed to be little risk of great upheaval at a Catholic school like Notre Dame, but Father Hesburgh knew that he couldn't take the risk by being silent on the matter.

Father Hesburgh recalled an unwelcome telegram from President Nixon a week later. He wanted Father Hesburgh to advise Vice President Spiro Agnew about federal legislation to address protests around the country. "My heart sank. Repressive legislation was the last thing colleges wanted or needed. I certainly wanted no part of it." He rushed word to Vice President Agnew before he was to meet with the governors regarding action.

The first thing I did was to prepare a cable opposing any and all kinds of federal action on the campuses. My position was that the universities and colleges should handle their own problems, make their own decisions, without the intervention of the federal government except upon invitation. My objective was to persuade the governors not to go along with any restrictive legislation on this sensitive issue.

Source: University of Notre Dame Archives.

The following fall, on November 18, 1969, the University had to enforce the fifteen-minute rule. But it was the first and only time. Twelve students were protesting the recruiters from Dow Chemical and the C.I.A. who were to arrive on campus. Father Hesburgh encouraged the dean of students, Father Jim Riehle, to be as lenient as possible while still following the fifteen-minute rule. After twenty minutes, he collected the IDs of the remaining ten and all were either suspended or expelled. Later, the expulsion was changed to a suspension, and all but one student returned to school the next semester.

Over time, Father Hesburgh quietly began to make the sort of changes the students requested, including increasing the enrollment of minorities and creating minority scholarships, loosening restrictions on alcohol on campus, and eliminating the curfew.

Some unwelcome news came from President Nixon the following spring. According to Michael O'Brien, "In a belligerent, provocative television speech on April 30, 1970, President Nixon justified sending troops into Cambodia in order to attack key North Vietnamese military targets."

Source: University of Notre Dame Archives.

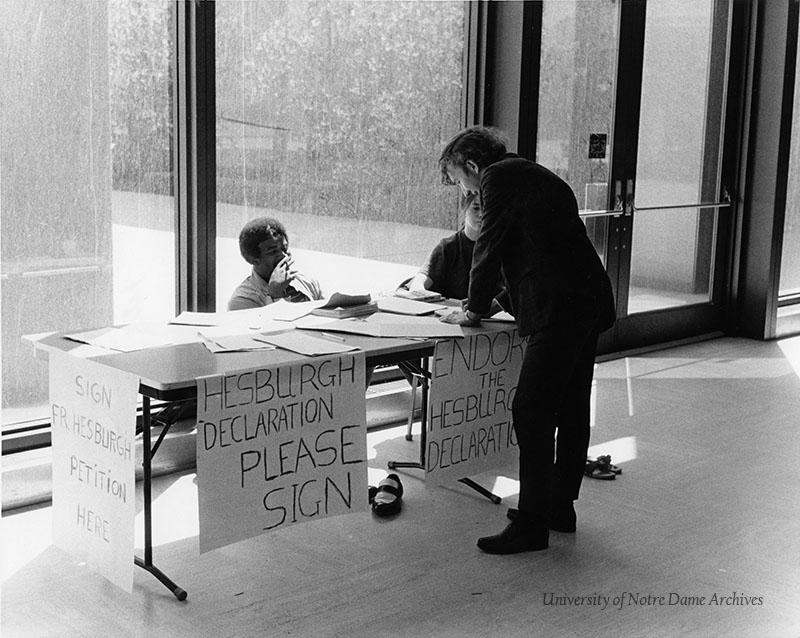

According to O'Brien, "On Monday, before a crowd of 2,000, Father Hesburgh delivered one of the most important speeches of his life." As Father Hesburgh spoke, word was spreading that four students protesting the recent invasion in Cambodia had been killed by the Ohio National Guard at Kent State. Father Hesburgh was against the war in Vietnam, and against violence anywhere. He also defended the R.O.T.C. program at Notre Dame, saying that the country needed a well-trained army that had a philosophical and ethical education. He suggested that together, they sign a declaration to send to President Nixon, asking for an immediate withdrawal of troops from Vietnam, as well as other peace-keeping measures. He was met with "thunderous applause."

Immediately following Father Hesburgh, a student named David Krashna spoke, encouraging the students to boycott all classes at Notre Dame and proposing a different education, one that really delved into the present day crises. He was met with the same reaction from the crowd. The students went forward with the signing of Father Hesburgh's declaration, as well as getting the support of 23,000 people within the South Bend community. As promised, he mailed the declaration and signatures to President Nixon. The students proceeded with the boycott, joining students across the country who were doing the same.

But at Notre Dame, this wasn't simply a boycott. This was an opportunity to come together as a Catholic community. According to O'Brien, "On Wednesday of suspended classes a thousand people took part in a Mass on the Main Quad." And the next day,

One of the most impressive events during the seven days was the community liturgy held on Ascension Thursday (May 7) with Fr. Ted as the principal celebrant. Every element of the campus-faculty, students, clerks, secretaries, alumni-crammed into Sacred Heart Church to hear Fr. Ted eulogize the slain students at Kent State and plead for a society in which "ballots replaced bullets" for American youth.

Father Hesburgh recalled, "It seemed that the predominant sentiment on campus switched over from violence to nonviolence in that one single week." Students were back in class shortly after. Classes in nonviolence began and grew every semester. Thousands of students signed up to take the courses. Father Hesburgh reflected on what got him, and certainly the University through these years, "... great good luck, the grace of God, and the very special love, respect, and caring that our people have always had for one another at this very special place called Notre Dame."