Caption

Caption

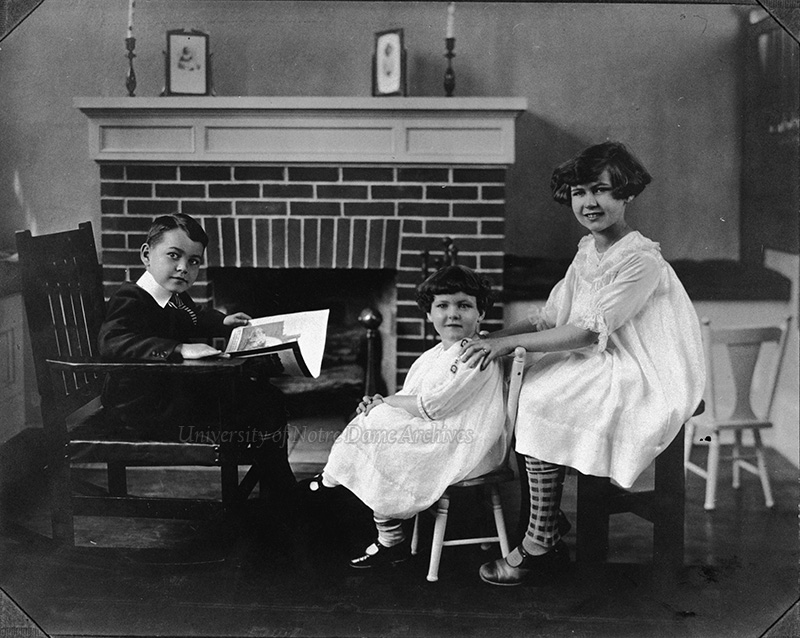

Source: University of Notre Dame Archives.

Growing Up

Catholic

Early Education

Father Hesburgh later described his upbringing as "a typical Catholic household of the period." He and his siblings attended Catholic school, wore uniforms, and were educated by strict religious sisters. The family prayed at home, were encouraged in their spiritual life and never missed Sunday Mass. Father Hesburgh was an altar boy and grew up under a strict moral code. He later quipped, "We never lied, stole, or cheated-at least we never got away with any such sins."

Ted was more of a reader than an athlete. He preferred to build model airplanes and dream of flying. At ten, Ted and his friend Eddie Naughton attended an air show in town with their fathers. Father Hesburgh later wrote, "The star attraction that day was a flier named Tex Perrin, and he was decked out like no one we had ever seen before: tight-fitting helmet, goggles, leather jacket, white scarf, flared cavalry pants, and high, laced boots. He was Lafayette Escadrille all the way. And we were impressed." The boys got a chance to go up with the stunt pilot on the "creaky biplane with a wooden propeller." He added, "The view was stunning-farms, woods, cars, people, downtown Syracuse, the neighborhoods, and, of course, Lake Onondaga, which is right next to the city. The ride could not have lasted more than fifteen or twenty minutes, but I was hooked for life." In June that same year, Ted was in New York City for his cousin's ordination at St. Patrick's Cathedral on Fifth Avenue when a parade was held to greet Charles Lindbergh, who had just returned from his solo flight across the Atlantic.

Despite his early love for flying, Father Hesburgh always wanted to be a priest. When Ted was in eighth grade, four missionaries from the Congregation of Holy Cross visited Most Holy Rosary Church. One of the priests, Father Tom Duffy, "made a great impression upon me," recalled Father Hesburgh. He encouraged young Ted to enter Holy Cross Seminary at Notre Dame. Though Father Hesburgh's calling was certainly encouraged at home, it was not something forced on him, nor was it something his mother wanted to rush. She told Father Duffy, "No dice," as Father Hesburgh later recalled. Father Duffy was concerned young Ted would lose his vocation. "She looked Duffy straight in the eye and said, 'It can't be much of a vocation if he's going to lose it by living in a Christian family.' Mother had spoken, and that was that."

High School

Father Hesburgh's high school experience was fairly typical. He took four years of English, Latin, and religion, and three years of history and French. He was a member of the high school literary guild, sang in the choir, and helped edit the school paper, The Rosarian, his senior year. In addition to his religious upbringing, he was very much formed by the sisters of the Immaculate Heart of Mary at Most Holy Rosary. He later recalled,

I will never forget those devoted nuns who ran the school, taught us discipline, rapped our knuckles, and hammered the lessons into our heads-Sister Augusta, Sister Justitia, Sister Q., Sister Delphina, and Sister Mary Veronica. ... all with master's degrees, they received about $30 a month in return for teaching full-time, overseeing many of the extracurricular activities, and keeping the church clean. I wonder how many high schools today are providing an education that is any better than the one I received between 1930 and 1934.

Like his father, Father Hesburgh was a voracious reader. He was influenced by his love of flying and naturally gravitated toward similar subjects in his reading. In 1982 Father Hesburgh reflected, "I read all the stuff that normal kids read, like Treasure Island, Robinson Crusoe. I was always interested in adventure, I was always interested in travel stories of various kinds." Later in high school, he wrote for the school paper and encourage his schoolmates to challenge themselves in their reading choices, and consider books on travel, adventure, and religion.

Father Hesburgh later reflected in his autobiography:

Equally important as any of our academic studies were the sense of morals and the personal values we learned throughout the twelve years of our primary and secondary school education. In those days all schools, public and private, sought to instill in children a long list of homespun values which were taught philosophically, if needed, to avoid overtones of religion: It is better to be honest than dishonest, better to be kind than cruel, better to help than to hurt someone, better to be patriotic than not.

Outside of school, Ted was very busy. He held various jobs, including: a paper route, hauling ashes from furnaces, mowing lawns, and selling watercress and nuts he found in the woods. During his senior year, he worked forty hours a week at a local gas station. In the summer, he participated in Boy Scouts and attended summer camp. Father Hesburgh recalled later, "I always liked the outdoors, the camping, the fishing. And as I got a little older, rabbit and pheasant hunting were just normal things." In the winter, he enjoyed tobogganing, skiing, and skating at Onondaga Park, and swimming at the local YMCA.

Father Hesburgh was not the rebellious type. His worst offense in high school was skipping school the first day of pheasant hunting his senior year. Father Hesburgh's sister, Anne, would later recall for a special edition of The Observer that even though he was "no troublemaker," he was "a character."

Source: University of Notre Dame Archives.

Although Father Hesburgh went to dances, parties, and dated, he could not let go of the idea of being a priest. He recalled,

[E]ven though I dated and partied as much as anyone in high school, I never wavered in my desire to be a priest. There were many nights when I'd roll in at 2 a.m. after having a good time and I'd just sit on my bed and say to myself, 'This isn't enough for me. There's something more that I need out of life.'

In the spring of his senior year, Father Hesburgh played the role of Christ in a school production of Christ's Passion. Two months later, he spoke at his commencement, thanking the sisters and reflecting on his time at Most Holy Rosary. "[W]e stand upon the threshold of the coming years while the bright future beckons. May it be a happy one-as happy as the years gone by!" And for Father Hesburgh, it was clear his future included the seminary. He and Father Duffy had stayed in touch throughout high school, and his senior year, he was given the choice of the seminary at Stonehill College in Massachusetts or the Holy Cross Seminary at the University of Notre Dame. He later recalled, "It took me about one third of a second to choose the dream of practically every Catholic schoolboy in the country."

Leaving Home

Of the siblings, Father Hesburgh was closest to his sister Mary. They were nearest in age and would often study together. She was a talented artist and earned a degree in fine arts from Syracuse University. Betty, as Father Hesburgh later described, "was the liveliest of the three." She inherited her mother's voice and sang at New Rochelle College. Anne was a tomboy who "did not care much for school," but she "had an incredible memory and could always beat the rest of us playing cards or in any game that involved remembering facts." In the fall of 1933, when Ted was a senior in high school, he finally got the brother he had always prayed for. Though Ted left for seminary when Jim (Jimmy) was only nine months old, the two grew closer over the years. It was difficult for Ted to move so far from home. He would miss his tight-knit family, and was quite homesick in the beginning.