Caption

Caption

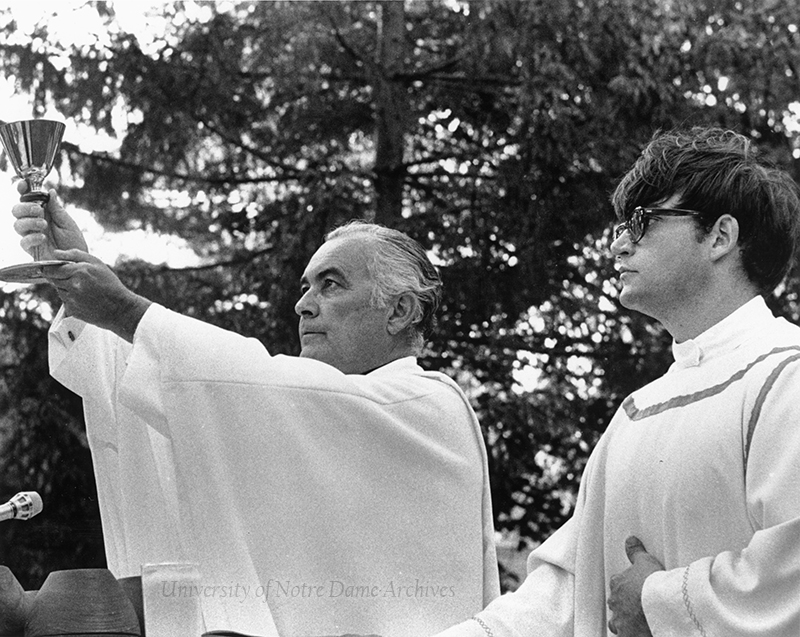

Source: University of Notre Dame Archives.

Community Life

The Congregation of Holy Cross, comprised of priests, brothers, and sisters, was founded in 1837 in France by Blessed Basil Moreau. In 1842, one priest and six brothers were sent to the United States to serve as religious educators, establish a religious community in Indiana, and later found the University of Notre Dame. According to the vocation's office website, Blessed Basil Moreau had a specific vision of how the community would look.

When he founded the Congregation of Holy Cross, Blessed Basil Moreau's vision and desire were to found a community on the model of the Holy Family. We were to be a family, bound together in the joys and struggles of life, drawing one another forward toward Christ through our living, working, and praying together. For Blessed Moreau, this union of our community was not simply an aid to our mission; it was an essential part of that mission in advancing God's kingdom here on earth.

From the time Father Hesburgh attended Holy Cross Seminary as a 17-year-old college freshman, until he died at the age of 97, he was a part of the Holy Cross Community. As a student at Notre Dame, he lived with, and partook in, community life with his fellow seminarians. They followed their own schedule of study and prayer, their own book of rules, and largely lived apart from the other students on campus. Father Hesburgh spent a year at Rolling Prairie, the novitiate boot camp in Indiana, where they built silos, harvested wheat and rye, studied, prayed, and spent most of the day in mandatory silence.

At age 20, Ted was off to Rome to study, where he lived in community and followed a strict schedule. The men in the house conversed, read, and prayed in French, and took classes, exams, and read in Latin at the University.

In May of 1940, Ted Hesburgh returned to the United States and attended Holy Cross College in Washington, D.C. for the next three years. In June of 1943, he briefly returned to Notre Dame for ordination into the priesthood. Then he was off to Washington, D.C. again, to work on his doctorate at Catholic University of America, which he completed two years later. While writing, he lived in community with other Holy Cross priests and assisted wherever he was needed.

In 1945, Father Hesburgh returned to Notre Dame to teach. He lived in Badin Hall with the veterans who had just returned from the war. In addition to teaching in the religion department, he was chaplain of the Veterans' Club and then Vetville, the community of former servicemen with families studying at Notre Dame. In 1948, as chair of the department of religion, he had to move into Farley Hall, where he was rector of 330 freshmen.

As a young priest on campus, he lived in dorms and participated in life there, but also regularly participated in common table and common prayer with his fellow priests. He was a priest, first, and he was part of a community of brothers committed to doing God's work on Earth. Some of his closest friendships were with his fellow brother priests.

Following his time at Farley Hall, as he was placed in administration, he was moved to Corby Hall in order to fully commit his time to his new roles, as executive vice president (1949) and then president (1952).

From the time Father Hesburgh was executive vice president in 1949, to the time he was moved to Holy Cross House when his health began to fail him in 2005, he lived in the same, simple room in Corby Hall. Father Hesburgh reflected in his autobiography, "I always had enough to eat, clothes to wear, a simple room in which to sleep, and money when it was needed for books or travel or incidentals."

Like other priests with various roles within Notre Dame and the surrounding community, he partook in community life whenever he was home. Often a late riser, Father Hesburgh would get up and ready at 10:00 or 10:30 a.m. Then he and Father Joyce would head to the Crypt at Sacred Heart, where each said Mass at a side chapel. After Mass, he would visit the Grotto and be off to the office by noon. Father Hesburgh would have lunch at Corby Hall or the Morris Inn and head back to his office for the remainder of the afternoon.

He would then join his brothers back at Corby Hall for evening prayer in St. Andrew's Chapel and then dinner in the main hall. Every week, he attended the Wednesday evening Mass at St. Andrew's Chapel. A fellow priest observed in O'Brien's biography of Father Hesburgh,

Usually, when he was on campus, he dined with his fellow priests at Corby Hall. 'I am sure he could be wined and dined every night of the year if he wished,' observed Fr. Griffin, 'but instead he recognizes his need to keep in touch with his roots in the community and to talk to people in the community and share his mission with them.'

The congregation was more than a community, but a family. And they supported one another. Despite differing perspectives of the religious, Father Hesburgh saw this as an opportunity to gather and engage in conversation and brotherhood.

After dinner, Father Hesburgh wouldn't typically stick around to play cards or socialize with the other priests but instead would return to the office for a late night, which he preferred for the quiet and absence of distraction. But at the Wednesday 5:00 p.m. Mass and Sunday evening social at Corby Hall, he was one of the regulars. In his retirement years, Father Hesburgh would stay to play bridge, or relax out on the porch in front of Corby Hall with the other priests, smoking a cigar.

Every January, Father Hesburgh was present for the annual Corby Hall retreat just prior to the beginning of the new semester. It was a three-night retreat that ran from Wednesday evening Mass until lunch on Saturday. There was opportunity for prayer, talks, Mass, community meals, and renewal of vows on Saturday. Holy Cross priests would also go on an annual eight-day retreat, taken individually.

Father Hesburgh would concelebrate with the other priests at Sacred Heart on big feasts, such as Easter. And he would be present the Sunday after Easter for priestly ordinations. The first blessing of the newly ordained is said to contain many graces, so Father Hesburgh would often ask new priests for the first. He would kneel before the newly ordained in the sacristy and humbly ask for their blessing.

Father Hesburgh was usually present for baccalaureate Mass and graduation, of course, but would leave shortly after to spend a week or so up at Land O'Lakes, Wisconsin, where the University owns 8,000 acres. He would be there in time for his birthday, on May 25. Much of the community would visit during that time, typically right after the spring semester and again toward the end of the summer.

Father Hesburgh loved to fish. He liked to claim the cottage right on the lake for peace and quiet. It was rustic, and fairly primitive, but it had screens on three sides. He would read (or later listen to books on tape), write (or dictate), pray, and fish. He would join the others for meals at the common dining room and prayer at the chapel. Father Bill Miscamble, C.S.C., recalled seeing him up at the lake. He would be puffing on a big cigar, say Mass around 4:00 p.m., enjoy a drink and early dinner, try to (unsuccessfully) help with dishes, and return to the lake in the evening to fish.

In 2005, as Father Hesburgh's eyesight began to fail, he was moved into Holy Cross House, which is the assisted living facility for priests on campus. His routine was relaxed, but every day before lunch, he would celebrate or concelebrate Mass in the chapel. He enjoyed the atmosphere there, where the priests helped each other. When he was strong enough, he would push those in wheelchairs, and when he was too feeble in the last couple years, others would push him.

One day, around the time Father Hesburgh was moved to Holy Cross House, Father Paul Doyle, C.S.C., received a call from Melanie Chapleau, Father Hesburgh's assistant. She asked if Father Doyle could assist Father Hesburgh from time to time with getting around campus, as well as traveling. The assistance from his fellow priests allowed Father Hesburgh to be active in his later years. Father Doyle mentioned that Father Hesburgh was always thanking everybody profusely for all of the help, but Father Doyle insisted it was "no chore" to assist his friend.

On March 4, 2015, during Father Hesburgh's funeral Mass at the Basilica of the Sacred Heart, Father John Jenkins, C.S.C., current president of Notre Dame, spoke during his homily about Father Hesburgh's commitment to the community.

For all the momentous events in which he played a role, all the honors he received, Father Ted always said that the most important day of his life was when he was ordained a priest, here, in this church, on Notre Dame's campus. As a religious, he was vowed to poverty and obedience. He lived in a small, austere room, shared meals and common prayer with the Holy Cross community, and will soon be laid to rest under a simple cross, undistinguishable from the graves of the Holy Cross brethren who lay with him.

In a blog post written following the death of Father Hesburgh, Father Brian Ching, C.S.C., reflected on the community of brotherhood that was evident at the funeral. Typically, the funeral procession from the Basilica to the Holy Cross cemetery is just attended by the Holy Cross community, but his was witnessed and attended by a great crowd.

I think so many were moved by the procession not just because it was a beautiful gesture for a great and wonderful priest-though it was-but also because the procession itself is such a meaningful gesture. It speaks volumes about who we are as religious and our commitment to the common life. Certainly our community is full of different personalities, ideologies, opinions, and points of view, and in our world these differences are often seen as reasons for discord and disunity. Yet we, in spite of our differences commit ourselves to a common mission and a common life through our vows. Though we are different in many ways, our life in community brings us together when it matters the most, as "brothers who dwell together in unity." ...

Our procession together to the community cemetery is a powerful, concrete, sign of our communal reality. Even in death our brothers are there with us to help us journey to the next life, to continue to pray for us and support us at those moments when we need it the most.

It is essential to our mission that we strive to abide so attentively together that people will observe: "See how they love one another." We will then be a sign in an alienated world: men who have, for love of their Lord, become closest neighbors, trustworthy friends, brothers. Constitutions, 4:42