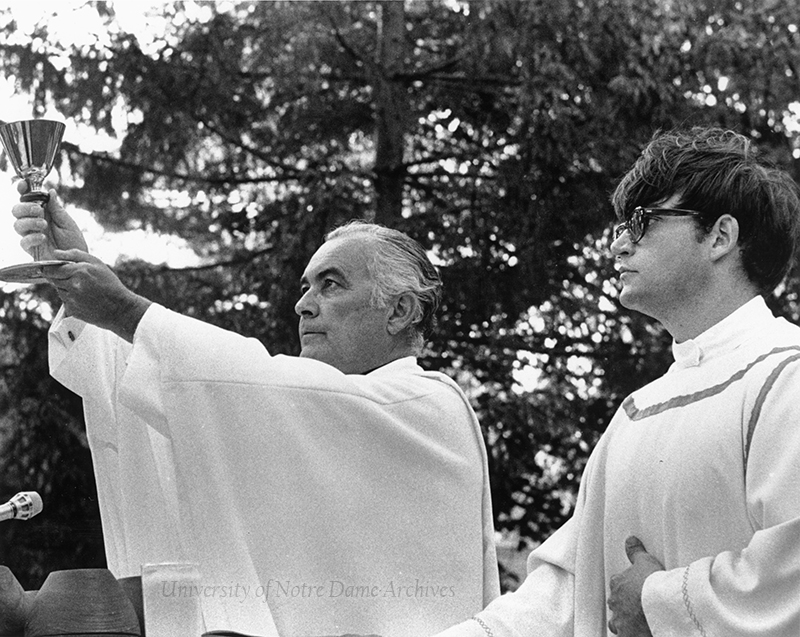

Caption

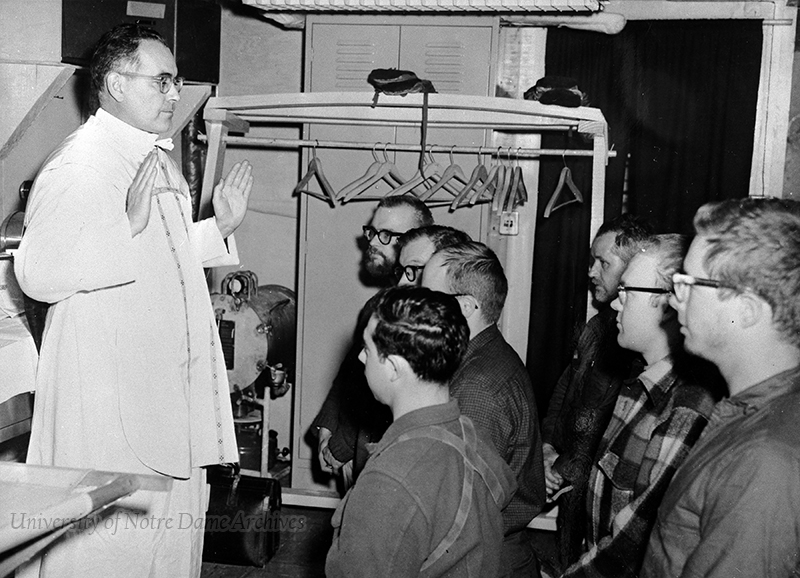

Caption

Source: University of Notre Dame Archives

Memorable Masses

Father Hesburgh believed celebrating Mass to be the most important part of his priestly duties, and the greatest gift he could offer. As a result of this commitment, through the course of his life, Father Hesburgh offered Mass in a number of interesting and unusual places. He once mentioned that he could write a book about all of the places he had said Mass. The following are a few stories he shared in God, Country, Notre Dame.

In Transit

As a young priest, in the summer of 1948, Father Hesburgh was given the opportunity to spend six weeks on a naval ship (R.O.T.C. aviation cruise) in the Pacific, where he would study and report on the naval aviation education of midshipmen, and assist as a chaplain. While traveling across country on the Southern Pacific Railroad, to board a ship in Alameda, California, Father Hesburgh had to brainstorm about how to say Mass, because he had a seat on the train's lower level with very little room. A Catholic couple came up to him while he was sitting in the train's club car and introduced themselves. They were traveling to Arizona with their two children and were staying in a state room. Before long, Father Hesburgh was set to celebrate Mass with them the next morning in their (relatively) spacious accommodations.

After Mass and breakfast, and seeing the family off, Father Hesburgh began to plan for the next day. He asked a conductor, who happened to be Catholic, if he could use the club car before it opened at six o'clock the next morning. The conductor woke him up early the next day and attended Mass in the empty car. As Father Hesburgh turned to give the final blessing, another conductor opened the door. Father Hesburgh recalled, "He looked at me as I gave the sign of the cross over him, and I thought he was going to drop right in his tracks. He didn't even come and challenge me, he just turned around and made a retreat out of the club car. And I quickly put my stuff back in the box and got out of there too."

During a layover in Rome, while on his way to Jerusalem, Father Hesburgh had about thirty minutes to spare. Unable to get to a church nearby, he raced to the service desk of a hotel in the airport. After explaining his situation, he received a key from the woman at the desk and quickly offered Mass. When he returned the key and asked how much he owed, the woman replied that he didn't owe anything. She added, "'You have sanctified my hotel.'" Father Hesburgh recalled, "I told her that I hoped one Mass would do it, thanked her, and hurried off to catch my plane."

In July of 1959, Father Hesburgh was traveling with his friend C. R. Smith and had a stop in Dallas, Texas, at 4:30 a.m. Father Hesburgh remembered asking an American Airlines employee for an empty office to say Mass. Father Hesburgh recounted an exchange with another airport employee while offering Mass there.

Just as I finished the ceremony, still dressed in my white robe, with my altar candles flickering in the dark, I was startled to see a bewildered baggage handler staring at me from the other side of the huge picture window.

"What are you doing there?" he called out.

"I'm offering Mass."

"Who for?"

"For the whole world."

That seemed to satisfy him, and he got back on his baggage tractor and left.

"Trying Circumstances"

One March day in Baltimore, Maryland, Father Hesburgh gave two lectures at Johns Hopkins University. That evening, he had dinner with Milton Eisenhower, then president of Johns Hopkins. An unexpected snowstorm hit the city, so Father Hesburgh couldn't make his flight that evening and was stuck at his friend's house for the night. He recalled in an interview, "You wouldn't believe it, but in an hour there was no way to get out of his house."

In this circumstance, since it was supposed to be a short trip to Baltimore, Father Hesburgh was unprepared to offer Mass the next morning. Milton lent him his tall fishing boots and long stadium coat, along with directions to a nearby chapel at Loyola University Maryland. After trudging a mile and a half through deep snow, Father Hesburgh arrived at the chapel at 7:00 in the morning, offered Mass, and then, made his way back to his friend's house.

In 1963, when Father Hesburgh was on the National Science Board, he traveled to Antarctica with a group of scientists and explorers who were fellow board members. The morning after arriving at the U.S. research center, McMurdo Station, he bundled up in thick layers and a parka and flew in a helicopter to an icebreaker 60 miles out at sea. The ship's captain refused to slow his operations for a priest to board, so the pilot had to carefully land on a moving icebreaker, which was charging at full speed to cut through ice that was 16 feet thick. When aboard, Father Hesburgh heard confessions, offered Mass, and had breakfast with the crew before taking off again by helicopter.

Source: University of Notre Dame Archives.

Shortly after returning to the station, he was flown to the South Pole. While landing, the plane hit an icy spike on the runway and nearly crashed, but thankfully the pilot was able to regain control. After walking a mile to the South Pole, Father Hesburgh returned to the station to hear confessions in a closet and offer Mass on a surgical table, which functioned as a makeshift altar in the tight quarters. After a few hours of sleep, Father Hesburgh said a blessing back at the South Pole in 34 degrees below zero. He recalled, "I pushed back the hood of my parka and said what must have been the shortest prayer on record. Most of the others present wisely left their hoods on." He then flew 800 miles to Byrd Station, to say Mass for the third time in 24 hours. He considered it a "record for the most Masses said in the shortest period of time, and under the most trying circumstances."

Father Hesburgh celebrated Mass in numerous places all over the world, with people of various backgrounds. He reflected in his autobiography, "Increasingly as the years have gone by, the more Masses I offer, the more evidence I see that this ancient rite has the power to change people, to change the world." Over the course of his seventy-two years as a priest, he undoubtedly had many more stories to share. To Father Hesburgh, though, this commitment was less about being able to tell fascinating tales, and more about serving God and allowing others to experience the Holy Spirit and the graces of the sacrament.