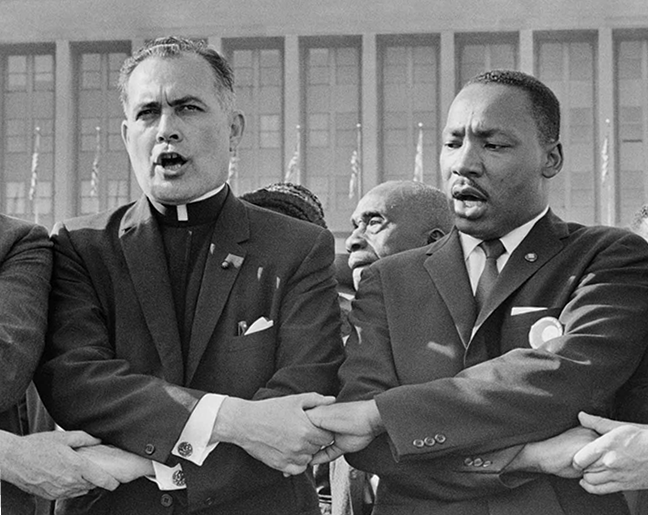

Caption

Caption

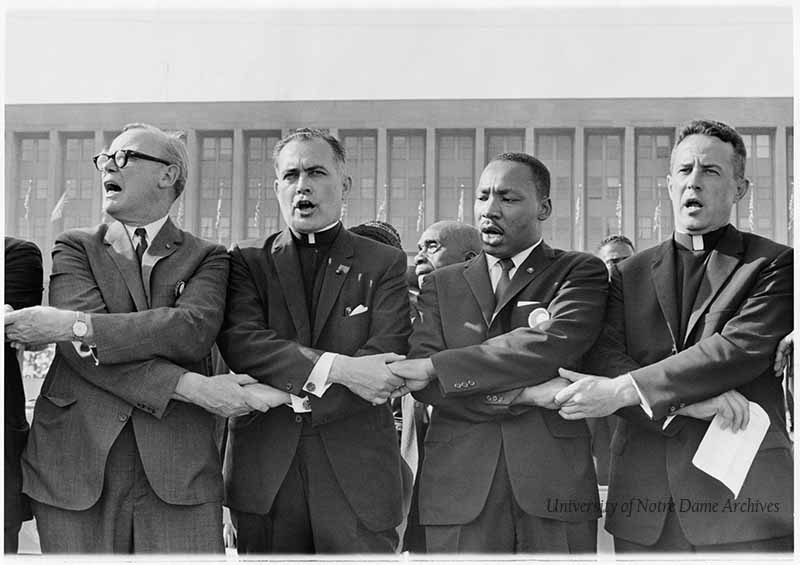

Source: University of Notre Dame Archives.

The Summer of 1964

The summer of 1964 was a pivotal time for the civil rights movement in America. As the year began, the proposed Civil Rights Act faced an uncertain future at best. President John F. Kennedy first proposed the legislation in a speech delivered on June 11, 1963. The act sought to outlaw discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin. It covered voter registration requirements and segregation in schools, at the workplace, and public facilities.

Source: University of Notre Dame Archives.

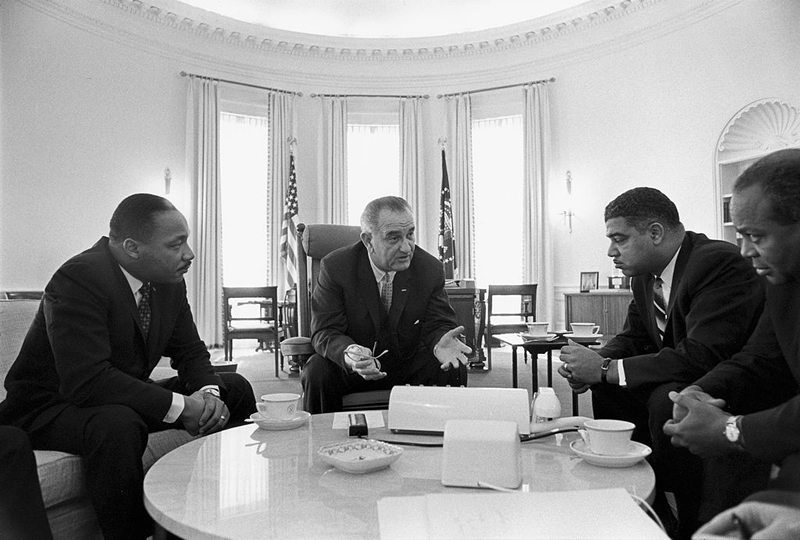

President Lyndon Johnson meets with Civil Rights leaders, including Martin Luther King, Jr, in the White House in 1964.

Source: Lyndon B. Johnson Library.

In the days following the November 1963 assassination of President John F. Kennedy, President Lyndon Johnson told Congress, "No memorial oration or eulogy could more eloquently honor President Kennedy's memory than the earliest possible passage of the civil rights bill for which he fought so long." Johnson was a skilled politician, who used his long experience as a congressman, and later senator, to navigate the complicated political issues and complex workings of Congress. Johnson also depended on civil rights activists across the county. Activists responded with rallies, sit-ins, boycotts, and protest marches. A wide coalition of civil rights leaders and activists demonstrated in public accommodations, from beaches and swimming pools, to bars and restaurants. One of the crucial groups Johnson depended on for leadership of this movement was the clergy.

The Illinois Rally for Civil Rights was planned and held in the context of these actions. On June 21, 1964, Soldier Field in Chicago hosted the Illinois Rally for Civil Rights. The principal speakers were Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., President and founder of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and Rev. Theodore M. Hesburgh, President of the University of Notre Dame.

Source: University of Notre Dame Archives.

The rally, whose operating costs reached $25,000, opened with two hours of jazz, gospel music, and entertainment, including a 5,000-voice choir led by gospel singer Mahalia Jackson. Nearly 150 various organizations promoted the event, distributing 1.5 million flyers in Chicago, and brought their members to the rally by bus. A crowd, estimated to be between 57,000 and 75,000, endured early rain and later sweltering heat in Soldier Field, while standing in solidarity for racial equality.

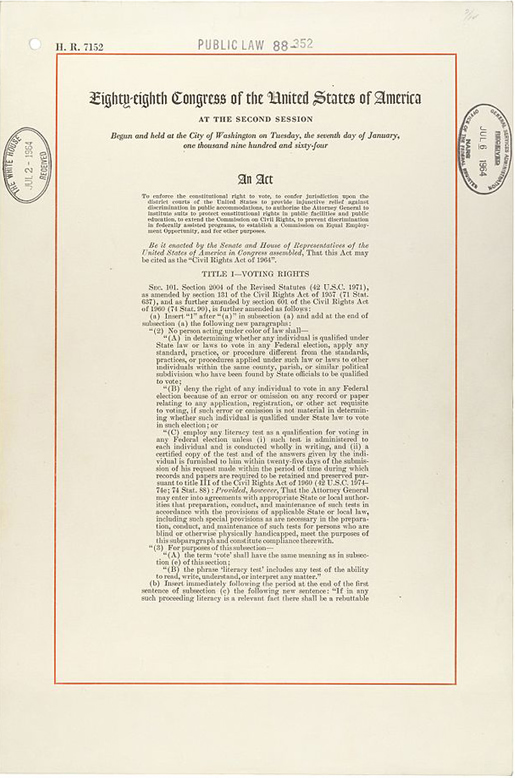

Source: National Archives and Records Administration.

King addressed the crowd that day, "We have come a long, long way in the civil rights struggle, but let me remind you that we have a long, long way to go. Passage of the civil rights bill does not mean that we have reached the promised land in civil rights." He stressed that the proposed civil rights bill alone was not enough- "vigorous enforcement" was essential to success.

James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner (left to right).

Source: Federal Bureau of Investigation.

King's words would certainly ring true that night, as three civil rights activists, who were participating in "Freedom Summer" as members of the Congress for Racial Equality (CORE), were murdered in Neshoba County, Mississippi. James Earl Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael "Mickey" Schwerner, who were attempting to register black voters, were shot at close range by members of the Mississippi White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, and aided by officers from the Neshoba County's Sheriff's Office.

After much struggle and opposition, and the untiring support of Johnson, the 1964 Civil Rights Bill was passed by both houses of Congress. Amid a federal investigation into the murder of the three civil rights workers, President Johnson signed the bill into law on July 2, 1964. This bill would serve as a lasting tribute to those who had lost their lives fighting for freedom, and as a much needed catalyst for change in America.