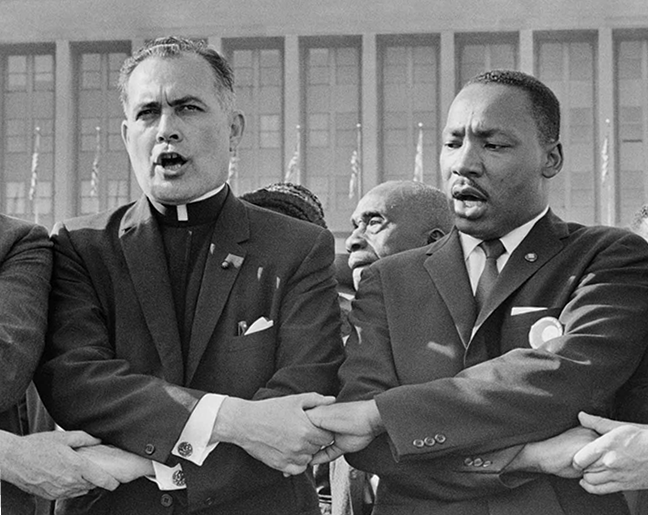

Caption

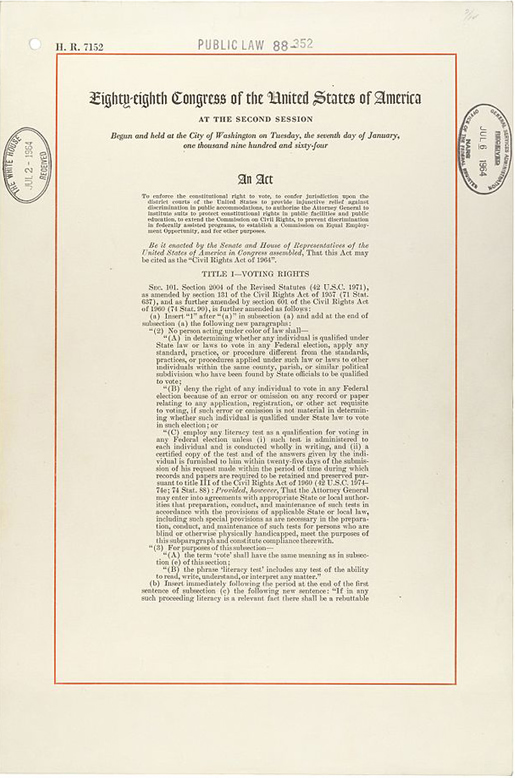

Caption

Source: University of Notre Dame Archives.

Father Hesburgh Appointed to U.S. Civil Rights Commission

Six million Americans whose skin was black were denied the right to vote; they could not walk in and get served a Coca-Cola in a drugstore of their choice, or go to a toilet of their choice, or take a seat of their choice on public transportation, or swim at any public beach, or get a job reserved for whites, or go to a school with white children, or be buried in a cemetery where white people were buried.

-Father Hesburgh, God, Country, Notre Dame

Such was the climate when President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed the Civil Rights Act of 1957, the first civil rights law passed by Congress since 1875.

Source: U.S. Navy.

In the fall of 1957, Father Hesburgh was standing on a corner outside the Sacher Hotel in Vienna, Austria, when he picked up and began to leaf through the latest copy of TIME Magazine. He came across a brief article about how President Eisenhower was creating a commission to study allegations of voter discrimination throughout the country. After returning home, Father Hesburgh recalled,

The first Sunday I was home, I got a call from Sherman Adams at the White House. He said, "Have you heard of the Civil Rights Commission?" I said, "Yes, I have." He said, "President Eisenhower would like to know whether you would accept appointment to the Commission for a two-year task?" I said, "Yes. I guess so." I never really learned how to say no to the President.

President Eisenhower felt Father Hesburgh would help balance out the three southern democrats and two northern republicans on the commission. The six-member U.S. Commission on Civil Rights was sworn in at the White House on January 3, 1958.

Source: National Park Service.

With a small staff and little money, the commission began researching the state of civil rights in the country, starting with voting, and later addressing other areas of discrimination. The commission faced many challenges from the start, including harassment and uncooperative and sometimes hostile judges and witnesses. In addition, as the commission began their work in the South, they found it difficult to find accommodations. They were barred from hotels and meeting places, even Maxwell Air Force Base in Alabama, because they had three African-American men on staff (one commissioner and two lawyers). One of the commissioners called President Eisenhower to complain. As Father Hesburgh described in his autobiography,

Ike blew a fuse. . . . He sat down and wrote a scathing executive order to the general at Maxwell, saying that the members of the commission would indeed be accommodated there. . . . That is what it took-an executive order from the President of the United States-to get the black members of our federal commission accommodated in federal housing at a federal military installation. Of course, it should not have been necessary. President Harry Truman had issued an executive order ten years earlier integrating all the armed forces.

It was clear as the commission continued that the law was not being upheld, and the work ahead would not be easy.

Recommendations Become Law

Father Hesburgh continued the difficult, yet rewarding, work on the commission for fifteen years, including four as chairman. He served under four U.S. presidents: Dwight D. Eisenhower, John F. Kennedy, Lyndon B. Johnson, and Richard Nixon. During the course of that time, the commission came out with five lengthy reports, involving voting, housing, education, employment, and administration of justice-two-thirds of the recommendations in those reports became federal law.

Source: United Press International.

Broadcast on national television, President Lyndon B. Johnson, joined by Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., signed the Landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964 into law. The act outlawed discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin, segregation in public places, and unfair voting practices.

Source: National Archives and Records Administration.

One year later, following the hearings in Mississippi, President Johnson signed into law the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which prohibited discrimination based on race, and contained provisions that regulated administration of elections in order to protect voting rights.

The Civil Rights Act of 1968, signed into law by Johnson a few years later, provided equal housing opportunities for people of every race, creed, and national origin, and made it a federal crime to "injure, intimidate, or interfere with anyone ... by reason of their race, color, religion, or national origin."

People thought highly of Father Hesburgh, as evidenced by the numerous articles circulating in newspapers when he was named Commission Chairman by President Richard Nixon in 1969. According to a Washington Post article, "Father Hesburgh ... has served on the Commission since its inception in 1958 and has been influential in shaping the panel as a forceful advocate in civil rights matters." A Washington D.C. News article stated: "He has been a longtime plowman in this field, and with his conviction, his experience and his unusual sense of objectivity, he strikes us as an ideal man for the job. ... [T]here is nothing rabid, or dreamy, or unrealistic about his philosophy. He simply has an exceptional understanding of decency and honesty."

His Legacy

When President Nixon asked Father Hesburgh to resign as chairman of the commission in 1972, it made headlines across the country. One writer for the New York Times observed, "Father Hesburgh and the commission have been critical of the Administration's enforcement of civil rights, as they had been of other administrations. But it was Father Hesburgh's biting attacks on the Nixon busing policy that raised the ire of Administration officials." Many applauded Nixon for ousting Hesburgh, but many more commended Hesburgh for his commitment to civil rights and exceptional work on the commission.

Father Hesburgh's fifteen-year tenure on the U.S. Civil Rights Commission was only the beginning for the fierce defender of civil rights. In 1973, with the aid of the Ford Foundation, he established the Center for Civil Rights at the University of Notre Dame (now the Center for Civil and Human Rights), which aspires to carry on the civil rights legacy of its founder. The Center's mission on its website reads:

The Center for Civil and Human Rights is founded on the belief that every human being, created in the image of God, has a dignity entitled to respect and protection. In all of its efforts, the Center stands in solidarity with the oppressed, the afflicted, and the vulnerable and seeks to secure their human rights and the conditions for their flourishing.