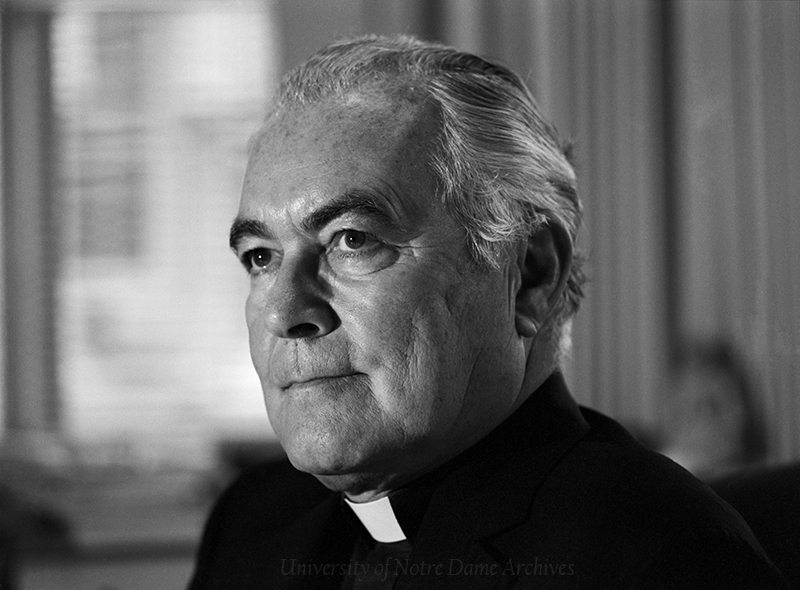

Caption

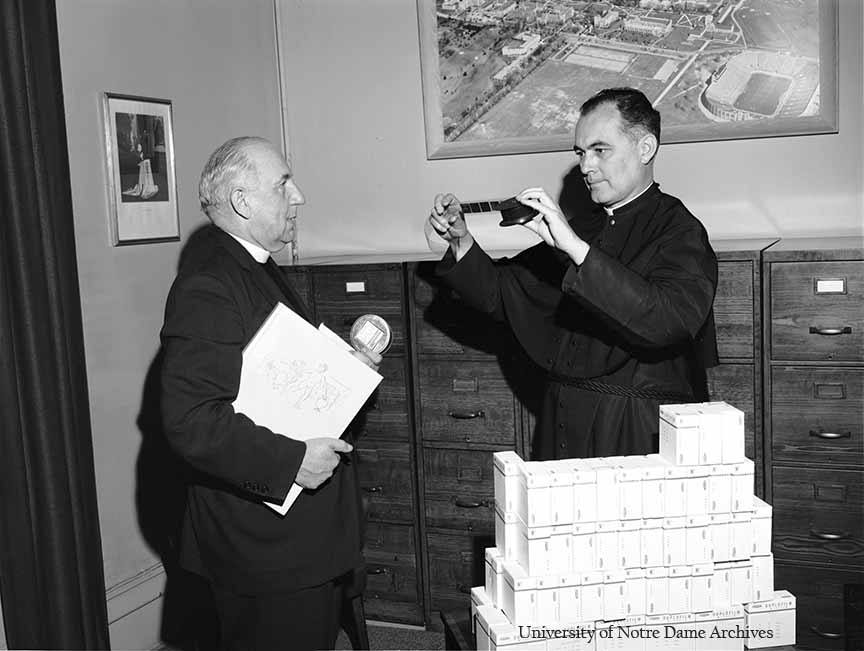

Caption

Source: University of Notre Dame Archives.

Teaching, Research, and Faculty Growth

The Vision

Beginning in the 1930s, when Theodore Hesburgh was an undergraduate at Notre Dame, changes were being made to improve the University. Soon after the newly ordained Father Hesburgh returned to campus after completing his doctorate in 1945, Father John J. Cavanaugh, C.S.C., became president and began dramatically transforming the administration.

In 1949, when Father Hesburgh was named executive vice president, much of the responsibility of running the University was placed on him. He later recalled Father Cavanaugh having said to him, "Ted, I'm really going to load it on you, and you're going to hate me, but best you learn in a hurry." Incremental changes had been made in the two decades leading up to his presidency, but it was really Father John J. Cavanaugh who set up the University in such a way for Father Hesburgh to accomplish as much as he did.

As he took office as president in 1952, Father Hesburgh soon had a vision for the University of Notre Dame. "I envisioned Notre Dame as a great Catholic university, the greatest in the world!" And he discovered what it would take to achieve this vision. "To be great, a university needs a great faculty, a great student body, and great facilities. In order to have those things, it needs a substantial endowment, which means you have to learn how to raise money-lots of it."

Father Hesburgh later recalled writing the following description of the state of the University in applying for a grant:

Our student body had doubled, our facilities were inadequate, our faculty quite ordinary for the most part, our deans and department heads complacent, our graduates loyal and true in heart but often lacking in intellectual curiosity, our academic programs largely encrusted with the accretions of decades, our graduate school an infant, our administration much in need of reorganization, our fund-raising organization non-existent, and our football team national champions.

Higher Academic Standards

Father Hesburgh said Father James Burns, C.S.C. (University President from 1919-1922), who had his doctorate in the history of education, was directly responsible for Hesburgh's studying in Rome and then going on for his doctorate. The Notre Dame curriculum was slowly improving over the years, but in some disciplines, the students were receiving a high-school level education, including in the religion department. Father Burns' solution was to send the young priests and seminarians to work on their master's degrees and doctorates. When Father Hesburgh and others returned with their advanced degrees, they were encouraged to write their own courses and curriculum. In fact, Father Hesburgh and his friend, Father Charles Sheedy, ended up writing and publishing textbooks. This wasn't just a problem at Notre Dame; there simply weren't university-level textbooks available for Catholic theology in the 1940s.

When Father John J. Cavanaugh was president, from 1946 to 1952, he began to make some sweeping changes at Notre Dame. He was reorganizing the administration and raising standards for both students and faculty members. He selected Father Hesburgh as executive vice president in 1949, and put him in charge of the reorganization. This included changing department heads and deans who were underperforming. The business school was one of the colleges that was tackled first. "When I became president, it was called 'the Yacht Club,' and it wasn't meant as a compliment. The school was kind of drifting. Perhaps it was nothing to apologize for, but it wasn't progressing either." They gathered some of the best business educators from around the country to learn how not only to succeed as a business school but become the best and started to implement those changes. Father Hesburgh quickly replaced the dean. He later recalled the bold yet necessary move, "It all boils down to people. I believe in loyalty, but I also believe that if you get the right guy in charge, everything else falls into place-better students, better faculty, a better college." Hesburgh and Cavanaugh were serious about transforming Notre Dame.

The law school saw similar changes. Father Hesburgh recalled how Father Cavanaugh "wrangled the resignation of the dean of the Law School, who was an enormously attractive man and a popular teacher, and replaced him with Joseph O'Meara, an outstanding lawyer from Columbus, Ohio." O'Meara then expelled half of the students. "He wasted no time in tightening up everything: entrance requirements, curriculum, exams, and new standards for faculty performance." It was clear that O'Meara was the right man for the job. "By the time he had finished, he had changed the place from a rather easy-going gentleman's club to a demanding, earnest school of law."

Father Hesburgh inherited a University that was advancing and on its way to becoming as well known for its academics as its football team. The University was changing and Father Hesburgh was extremely proud. "My new deans all had two things in common: They had high aspirations for Notre Dame and they had the ability to lead. John Cavanaugh used to say that leadership was a very simple matter. All you needed was a vision of where you wanted to go and the ability to inspire a lot of people to help you get there."

Source: University of Notre Dame Archives.

Research

Father Hesburgh also understood the need for faculty to keep up with scholarship and complete research in their fields. According to Kerry Temple in his book O'Hara's Heirs: Business Education at Notre Dame, "A school's reputation, it was said, depended upon that scholarship, the publications of its faculty, and their participation in professional activities."

If they were going to be a great university, they would need to continually excel. Soon, the University was on its way. Father Hesburgh recalled the early years of his presidency in God, Country, Notre Dame,

Year after year we attracted better people, bigger grants, more endowed chairs, and raised our admission standards for students. We let it be known that we expected more from our deans, our faculty, and our students than ever before.

With the funds, the University could provide the necessary staff, equipment, and other resources needed to pursue serious research. And a faculty who shared a common vision for the University's future was key.

Source: University of Notre Dame Archives.

Faculty Growth

Over the years, Father Hesburgh was committed to the advancement and growth of the University of Notre Dame. This meant increasing faculty salaries starting in the 1950s and maintaining some of the most competitive salaries in the country. During that time, Notre Dame established a Distinguished Professors Program to attract some of the best scholars. He recalled in God, Country, Notre Dame,

We barnstormed around Europe and America, searching for the right people to come full-time or as visiting professors. It was a long process, but it is really amazing what the very best people can do for a university. They attract other outstanding professors. They attract outstanding students. And they attract more research and endowment money for more special faculty. When I retired as president, we had established more than one hundred named distinguished professorships, each one endowed for a million dollars or more.

In Father Hesburgh's thirty-five years in office, he helped to transform Notre Dame, which by then was in many ways the great Catholic university that he had imagined in 1952.