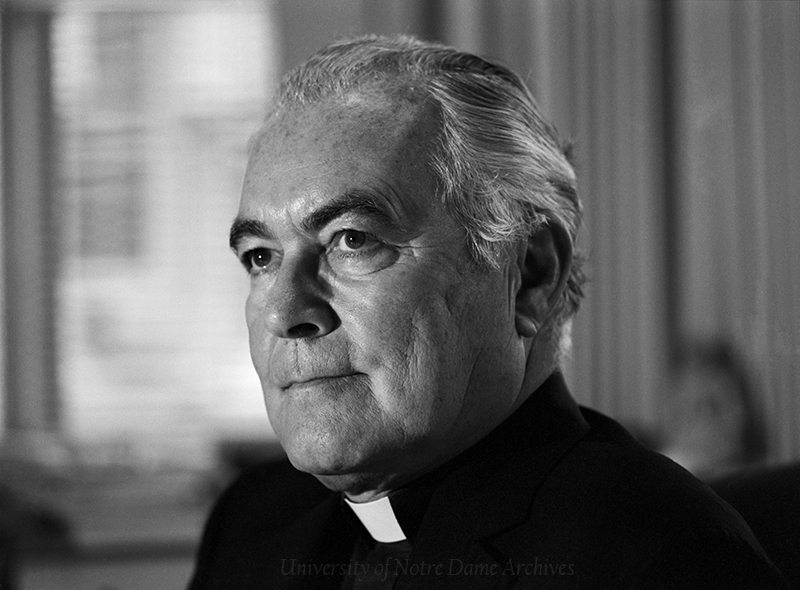

Caption

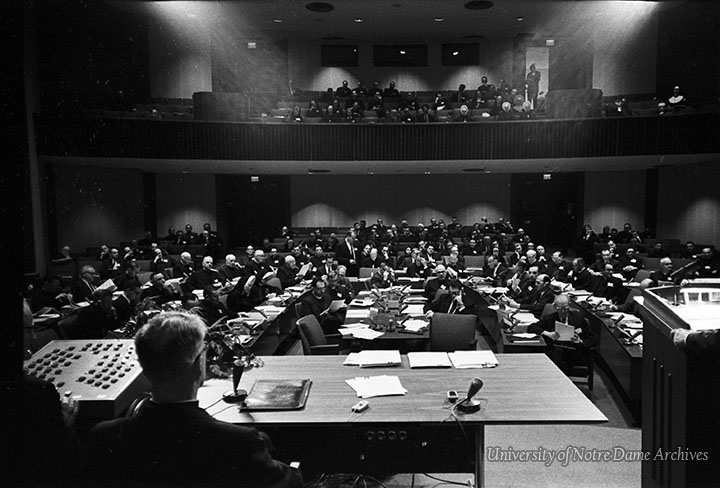

Caption

Source: University of Notre Dame Archives.

Building the Department of Theology

When Father Hesburgh started teaching in 1945, Notre Dame did not have a Department of Theology. Father Hesburgh taught in the Department of Religion, which offered five courses-four of them were required for all Catholic students. Of the nine professors in the department, three had bachelor's degrees in Sacred Theology, three had master's degrees, one had a Ph.D. in psychology, one had a Ph.D. in Scripture, and one had a doctorate in Sacred Theology-Father Hesburgh himself.

The department did not offer courses for graduate students. Undergraduates could not major in religion. The annual Bulletin of the University of Notre Dame clearly stated the purpose of the department:

The Department of Religion provides for undergraduates required courses of instruction in the principles of Catholic morality, the Sacraments, Catholic dogma, and Christian apologetics, and elective courses in Scripture, social problems, and Catholic lay leadership. The purpose of the courses is to develop the religious life of the student and so prepare him for the duties of an educated layman.

The Bulletin for 1945-1946 does not list any elective course in Scripture, but does list one elective course in "Catholic Lay Leadership." It makes clear that all Catholic freshmen must take "The Commandments of God" and "The Sacraments," and that all Catholic sophomores must take "Christian Apologetics" and "Catholic Dogma." Father Hesburgh taught dogma.

In 1982, when Richard Conklin interviewed him, Father Hesburgh gave his opinion of the religion curriculum at Notre Dame at this time:

I thought it was more geared to high school than to university students. I thought university students ought to be challenged to know what the Church really teaches about the Incarnation or the Trinity or great moral questions. We shouldn't duck them. They ought to be as sophisticated in their approach as they are in mathematics or psychology or physiology.

He also had a low opinion of the textbooks then in use: "There were really no books of any consequence for college students in theology."

Department of Religion, and undergraduates could major in Religion. Father Hesburgh solved the textbook problem by writing his own, God and the World of Man, published by the University of Notre Dame Press in 1950. In his autobiography, Father Hesburgh noted, "But we still had a long way to go. Even after things started to turn around in the theology department, the courses were geared more to a high school level."

When Father Hesburgh became president in 1952, his ambition to make Notre Dame a great university led to efforts at improving the faculty and reforming the curriculum. His 1982 interviews indicate that he always kept the Catholic character of Notre Dame in mind and therefore regarded improvements in theological education as among the most important. He told Richard Conklin in 1982: "Today, there are probably thirty-five doctors of theology at the university. So it's a far cry from what I began."

In Hesburgh: A Biography Michael O'Brien writes:

As Fr. Ted began trying to mold Notre Dame into a major Catholic university, he reflected on John Henry Newman's great classic of educational literature, The Idea of a University. . . . The Idea of a University suggested a vision for a Catholic university in which the liberal arts played a central role and teaching was important. Fr. Ted also liked Newman's description of intellectual virtues, including "the ability to tolerate fundamental diversity of beliefs and values without sacrificing conviction." Moreover, the one pervading thought that characterized Newman's writings on education was the belief that a university that teaches everything else but neglects theology, "the science of God," was not committed to being a true university. Newman stimulated Fr. Ted to build a great Theology Department. "I got some very good ideas [from Newman]," he later said, "especially on the primacy of theology in a Catholic university."

In the Graduate School Bulletin for 1959-1960 the Department of Religion announced a master's degree:

The program toward a Master of Arts in Theology is designed to give the student a thorough knowledge of the major areas of Catholic Theology, and sufficient mastery of the spirit, method and instruments of theology to enable him to carry on research in view of a doctorate.

In the 1960-1961 Bulletin the Department of Religion becomes the Department of Theology, which "provides required courses for undergraduate students" and "also offers graduate programs leading to the Master of Arts Degree in the general field of Theology and the specialized field of the Sacred Liturgy."

When Father Hesburgh became president, he saw to it that the lectures from the liturgy program were published as a series of books. Michael Mathis, C.S.C., was a pioneer in the liturgical movement. He taught in the Religion Department from 1938 to 1941, and found it frustrating that the curriculum allowed no development of his interest in liturgy.

Father Hesburgh founded the liturgical studies program in the summer school at Notre Dame in 1947. Starting in 1948, when he received permission to elevate the program from undergraduate to graduate education, he invited the most prominent figures in the liturgical movement to teach at Notre Dame-Donald Attwater, Cornelius Bouman, Louis Bouyer, Jean Danielou, Godfrey Diekmann, Aloys Dirksen, Gerald Ellard, Hugh Farrington, Balthasar Fischer, Jean F. Gy, Martin Hellriegel, Johannes Hofinger, Joseph Jungmann Edmund Kestel, Boniface Luykx, Thomas Michels, Christine Mohrmann, Sr. M. Pudentiana, H. A. Reinhold, Walter Knight Sturges, Ermin Vitry, Helen Walsh, and others. Though many considered liturgical studies an eccentric obsession, the early development of the program made possible the specialization announced in 1960.

The liturgical movement in these years prepared the way for one aspect of the Second Vatican Council. Recognition of the lay apostolate, even in the early curriculum of the Religion Department, qualifies as another anticipation of later developments. In his doctoral dissertation, Father Hesburgh wrote about the Mystical Body of Christ and the place of the laity in the Church. He told Richard Conklin how the Apostolic Delegate asked him to send two copies of his thesis to Rome via air mail: "There are a few lines in the Vatican Council which are almost verbatim from my thesis. . . . I figured I was either going to get shot or used. I guess I was used."

But in the same interview, Father Hesburgh acknowledged that his text book would need extensive revision to survive in the years after Vatican II:

In a sense that's what Father Dick McBrien has done. He brought the old classical theology up to speed with Vatican II and the changes that took place there. . . . from a monarchical to . . . a living-body approach.

The increased professionalism of the Theology Department should not mean any dilution of Notre Dame's Catholic character. According to Michael O'Brien, Father Hesburgh was quite clear about religion's place at Notre Dame.

What role should religion play at Notre Dame? he was asked. 'We do not hold that piety is a substitute for competence, but it should not be divorced from competence,' he said. 'If a man is responsible to God he will be responsible to his neighbors, his family, and his country. Our emphasis on religion isn't something that is tacked on to the program, but a fiber running through our entire educational structure.' Religion was important, he added, but it should not be taught in a 'sentimental or superficial way.'

In contrast to the nine professors listed in Father Hesburgh's first year as a professor, in his last year as president (1986-1987) the Theology Department listed over forty professors. In contrast to the five courses offered in his first year, in his last year the department listed forty undergraduate courses and over a hundred graduate courses.

During Father Hesburgh's years as president, the Department of Theology developed from modest beginnings into a highly respected source of original research, and a place where doctoral students can find excellent programs in theological inquiry, Christianity and Judaism in antiquity, and liturgical studies. Master's degree students can prepare for more advanced study or for ministry in the Church. With an ecumenical faculty of eminent theologians and scripture scholars, the department attracts highly qualified students and prepares them for professional careers.