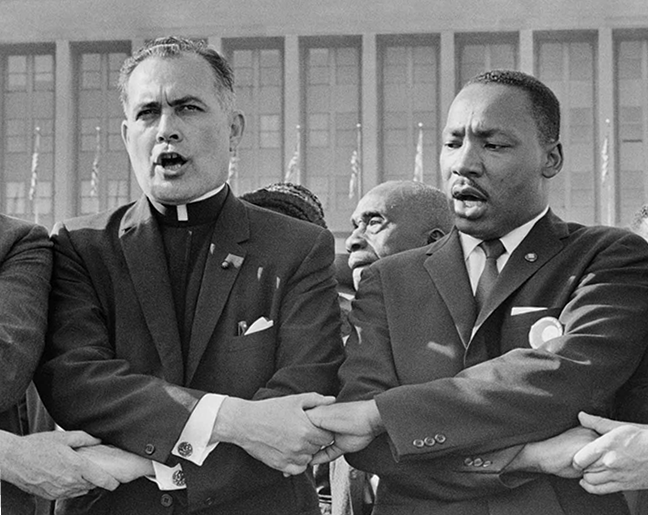

Caption

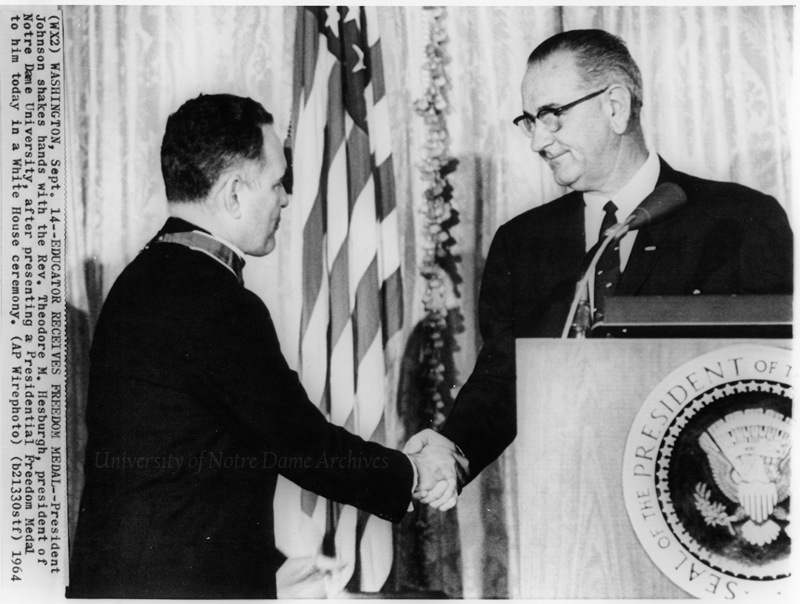

Caption

Source: University of Notre Dame Archives.

From Eisenhower to Nixon

Father Hesburgh served on the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights under four U.S. presidents: Dwight D. Eisenhower, John F. Kennedy, Lyndon B. Johnson, and Richard M. Nixon. The commission was an independent agency, which reported to the president and Congress. They would meet with each president, giving updates on their work, and would submit a final public report at the end of every two years. Some presidents were more involved than others. All claimed to be committed to the cause of civil rights in America, none would prove to be completely unwavering in that commitment.

Eisenhower

Father Hesburgh was just five years into his presidency at Notre Dame and just forty years old when he was appointed by President Dwight D. Eisenhower to the Civil Rights Commission in 1957. President Eisenhower had selected Hesburgh several years prior, in 1954, to be on the National Science Board, so he knew the young college president was up to the task.

In 1957, Eisenhower signed the first Civil Rights Act in more than eighty years; an act that showed the president's commitment to civil rights. Hesburgh recalled his first meeting after being sworn in.

After we had been sworn in and the usual number of photographs had been taken, the President sent everyone else out of the office and sat down to talk with us. At that point, he was quite serious and he said: "This problem that you are addressing yourselves to is the most serious domestic problem on the whole American scene today. To the extent that we can solve this problem, we will be worthy to hold up our heads in the company of the other nations of the world-to the extent that we bring some light to this problem, we will be qualified to work on world problems-because it's rather ridiculous to take a world posture on the meaning of democracy and equality and equal opportunity and not to practice it at home."

The commission had a productive first two years, collecting numerous facts and sworn testimonies, holding hearings all over the country. Father Hesburgh later articulated his sense of Eisenhower's commitment:

I always felt that Ike was one of the most underestimated presidents in modern times. He got things done, and he did not shout about it from the rooftops. ... I would not say Ike was a great champion of civil rights, per se, but he possessed a very strong sense of fairness and justice, which he applied to all people regardless of race, origin, or color of skin.

Kennedy

Source: University of Notre Dame Archives.

President Kennedy was cautious when it came to civil rights. He once asked the commission to hold off an important civil rights hearing for political reasons, which they did. In the commission's 1961 Report, Father Hesburgh voiced his frustration with the president and administration. "Personally, I don't care if the United States gets the first man on the moon, if while this is happening on a crash basis, we dawdle along here on our corner of the earth, nursing our prejudices, flouting our magnificent Constitution, ignoring the central moral problem of our times, and appearing hypocrites to all the world."

It wasn't until June of 1963, toward the end of Kennedy's life, that he would take on a more active role in the civil rights movement. No longer able to ignore the hatred and violence aimed toward minorities in America, the president addressed the nation on June 11. Kennedy's words seemed to be a response to those of Martin Luther King, in his famous "Letter from Birmingham Jail," written two months before. Among other things, King voiced his disappointment for inaction and delay in recognizing African Americans' rights as citizens. Kennedy called the nation to see the oppressed minority and every person's moral obligation to defend and promote freedom for all. He announced a new civil rights bill that he was submitting to Congress.

Johnson

Source: University of Notre Dame Archives.

On November 22, 1963, following the assassination of John F. Kennedy, Lyndon B. Johnson was sworn in as president aboard Air Force One. Johnson proved to be a fierce defender of civil rights. He worked with the commission and other civil rights groups in order to bring about change. One of the first changes Johnson implemented was hiring African-American men to important positions within the administration. He then appointed the first African-American woman to the civil rights commission.

The 1960s saw a great increase in racial violence and unrest, and the commission saw it as their role to address the riots taking place around the country. Johnson disagreed and wanted the commission to focus on education and other areas of civil rights instead. Though the commission felt it was being prevented from addressing more pressing concerns, members attempted to create more transparency at the state and local levels with regard to civil rights.

President Johnson signed the 1965 Voting Rights Act into law, which protected voting rights and regulated elections. Three years later, he signed the Civil Rights Act of 1968 into law, ensuring equal housing opportunities to all.

The commission's life was extended beyond two years under Johnson, first for four years, and then for five. The continuity would prove important in the 60s, amidst the turmoil that gripped the nation. The country lost its president, and the civil rights movement lost one of its most influential leaders, Martin Luther King, Jr.

This was a difficult decade for the commission, but despite the numerous frustrations and setbacks, the movement was making great strides. The commission would expand its efforts and begin to address discrimination against Latinos, Native Americans, Asian Americans, and women.

Father Hesburgh said in an interview, "I've got to say that in spite of all the things you hear about this president and that, if the gauge is civil rights and commitment to do something about social justice, you've got to give Lyndon Johnson high marks." And in his autobiography, he echoed, "Without Lyndon Johnson's courage and vision upon taking office, we would not have come as far as we have today on civil rights and human rights."

Nixon

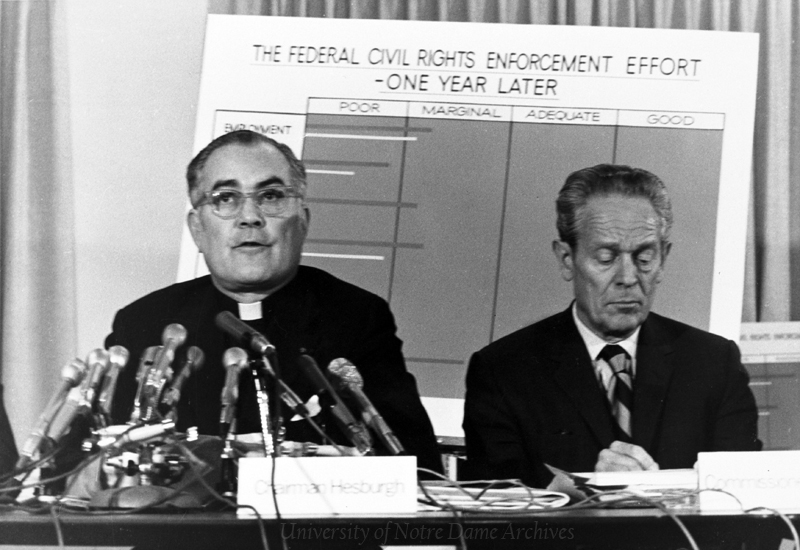

Source: University of Notre Dame Archives.

Shortly after President Richard Nixon took office, Father Hesburgh paid him a visit. Father Hesburgh recalled saying in the private meeting, "'I've been on this commission for eleven years. It's a very grueling business. I think I may be running out of ideas. I think it needs a whole new look, maybe new leadership. And I would like to request that you accept my resignation as of, well, as soon as the new guy gets aboard, the new chairman.''' Nixon responded that he would think about it. "I got a call from his people about two weeks later asking if I would accept the chairmanship. I said, 'Jeepers, I asked to get off and he makes me chairman.'"

Father Hesburgh began the first of four years as chairman and would see some positive changes taking place. President Nixon hired several African-Americans to his administration, and increased the budgets of civil rights agencies, including the civil rights commission. He gave funds to local school districts to address desegregation; however, lack of oversight led to the misappropriation of those funds. Nixon hired more Hispanics and created various agencies to meet the needs of Latinos throughout the country. Whether or not Nixon's intentions were purely altruistic, he was promoting change.

However, Father Hesburgh and the commission would soon discover that President Nixon's administration was often working against them and would do little to advance the cause of civil rights in America. The administration was not effectively enforcing the fair housing law and was requesting delays in school integration. The Justice department and various agency heads began stalling on civil rights initiatives.

It was suggested to Nixon that the commission look at the federal government and its enforcement of civil rights, and Nixon agreed. The commission studied forty of the main government departments and agencies for a year and prepared a report to be released to the public just prior to the mid-term election. Thirty-nine of forty agencies were labeled as performing poorly, the lowest possible score. Nixon's lawyer, who also happened to be a friend of Father Hesburgh, pressed him to delay release of the report so he could come up with a plan for action. Father Hesburgh, respectfully, refused, as the commission was an independent agency and, having announced it a year ahead of time, everyone was awaiting the results. He said, "If the facts hurt, then the administration should get busy and do something to correct the causes."

Father Hesburgh provided a summary of the report and briefed the media a few days before release. In the report, the commission recognized that the president was key in steering the country in the right direction.

[A]chievement of civil rights goals depends on the quality of leadership exercised by the President in moving the Nation toward racial justice. The Commission is convinced that his example of courageous moral leadership can inspire the necessary will and determination, not only of the Federal officials who serve under his direction, but of the American people as well.

The report received a lot of publicity, more than any previously. Though the report was critical of the administration, it was clear that the problem was not a new one.

Despite the negative report on the federal government, there were other issues at the forefront of Americans' minds, including the economy,the Vietnam War, and Richard Nixon's reelection in 1972. But the administration's ire over the commission's role in its public embarrassment was apparent and would steadily increase during those two years up to Nixon's reelection. The commission followed up the 1970 Report with progress reports every two months. With few exceptions, the reports were largely negative and showed little advancement on the part of the federal government with regard to civil rights enforcement, and the administration did what it could to lessen the impact of these reports.

Soon after President Nixon was reelected he replaced Father Hesburgh, ending his 15-year tenure on the commission. Though his work serving on the commission was done, Father Hesburgh would continue the cause about which he was so passionate, and open the Center for Civil Rights at the University of Notre Dame.

Many years after, when Hesburgh was asked to speak at a dinner to which both former Presidents Nixon and Ford were invited, all the speakers before him addressed President Ford first, Hesburgh did not follow suit. He shook hands with and addressed Nixon first. "A minor gesture, yes, but it was not lost on Nixon. ... As one gets older, it becomes more apparent that forgiving and forgetting is much better than holding grudges. Besides, it is more Christian."