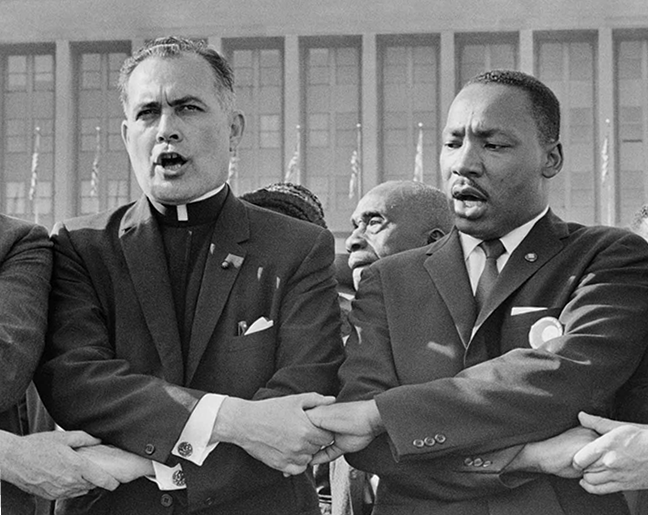

Caption

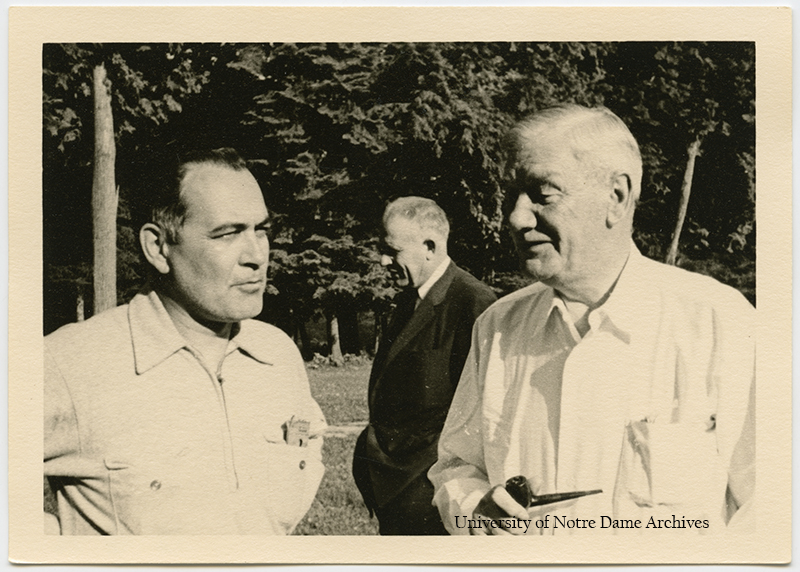

Caption

Source: University of Notre Dame Archives.

Civil Rights Report of 1959

Commission Findings

After the commission assembled the necessary staff to begin their work, they had a little over one year to complete their research and submit a report to the president and Congress. Through the course of the next year, the commission traveled around the country holding hearings on voting rights infringements, housing discrimination, and school segregation.

The commission conducted interviews and prepared to hold hearings. As most of the complaints they received regarded voting rights violations in the South, they traveled to Alabama, Mississippi, Florida, Tennessee, and Louisiana. African-American witnesses in these states testified about the many ways in which they were prevented from registering to vote. They were given incorrect information regarding where to register, had to wait in lines for hours, fill out long and complicated forms, had to find two registered voters to vouch for them, even if they could prove age and citizenship, were harassed, were threatened with or became victims of violence. White witnesses, who were called before the commission to speak, were often uncooperative, denying any form of prejudice or misconduct.

In 1954, in the famous case of Brown v. Board of Education, the Supreme Court determined that state laws were unconstitutional that provided separate public schools for black and white students. As the commission researched the state of public education in the South, they found that six southern states remained entirely segregated, and of the other southern states beginning to integrate their schools, progress was very slow. The commission held a conference in Nashville, Tennessee to discuss desegregation among the schools open to change. Cities and school districts making notable progress shared their successes and admitted the hardships in achieving it. Desegregation would require cooperation among various groups involved with education in a community-school boards, teachers, and parents-and a clear plan with open communication along every step of the way. The press would play an important role as well.

Complaints of housing discrimination took the commission to New York, Chicago, and Atlanta, where they held investigations and hearings. Only four states (Colorado, Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Oregon) and two cities (New York and Pittsburgh) had anti-discrimination laws in place with regards to the rental and sale of private and public housing. Most of the African-American population in Chicago and Atlanta, as in almost every other city, was limited to substandard housing in often congested areas.

Writing the Report

Knowing the scale of the task before them, the commission members and staff began drafting the report as soon as their work began in 1958. They opened the report with the history of civil rights in America. Then they organized their findings into three chapters-voting, public education, and housing-each beginning with a background history. Each chapter included recommendations, which they would vote on. It was clear that all of the commissioners were in agreement about the significant harm done to African-Americans throughout history and nearly all agreed on the need for federal action to uphold their rights as citizens.

There was space for individual voices and differing opinions throughout the report. These appeared at the end of each recommendation, where appropriate, or in footnotes, and the very end of the report included general statements by the commissioners. But the commissioners agreed that it was important to present a largely unified report. The commission was largely in agreement over solutions to voting rights, but there was more division with regards to public education and housing recommendations. In those areas, the commission admitted there was still much to be learned and rather than suggesting any sort of concrete changes, they recommended further research be done.

The Final Draft

One hot July day in 1959, when the commission was being prevented from holding hearings in Louisiana and had to prepare their final report for President Eisenhower and Congress, Father Hesburgh decided to suggest a much needed change of scenery. He arranged for all of them to fly to Land O'Lakes, Wisconsin, where the University owned 8,000 acres of land with 27 lakes. Father Hesburgh recalled,

Aboard the plane we settled right down to work on our final report. Hannah and the other commissioners huddled up in the front of the airplane. The staff members and I went to the back and started formulating the final resolutions, which would be the heart of the report. Our preliminary findings and conclusions already had been written in the cities where we had held the hearings.

In the evening, after working on the final recommendations for their report while on the plane, Father Hesburgh and the staff brought out the 12 recommendations to vote. Eleven of the 12 passed unanimously and one passed five to one. The commission officially submitted their final report in September of 1959.

The Country's Reaction

President Eisenhower was shocked by the nearly unanimous vote on the recommendations in the report. Father Hesburgh recalled, "I told Ike that he had not appointed just Republicans and Democrats or Northerners and Southerners, he had appointed six fishermen. I told him about Land O'Lakes and he commented, 'We've got to put more fishermen on commissions and have more reports written at Land O'Lakes, Wisconsin.'"

Predictably, the report received mixed reviews. As a New York Times article stated, "worthy of serious consideration by all men of good will." In another editor from the Richmond News Leader, it was considered "a work of propaganda, conceived by modern-day abolitionists, and published with all the zeal of the intolerant tent evangelist."