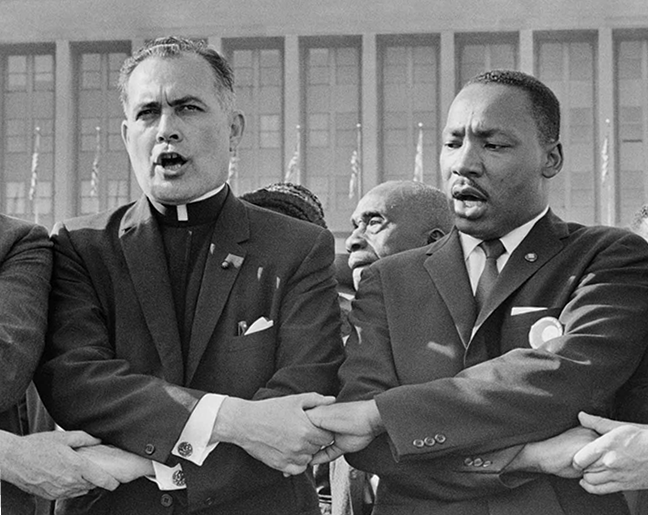

Caption

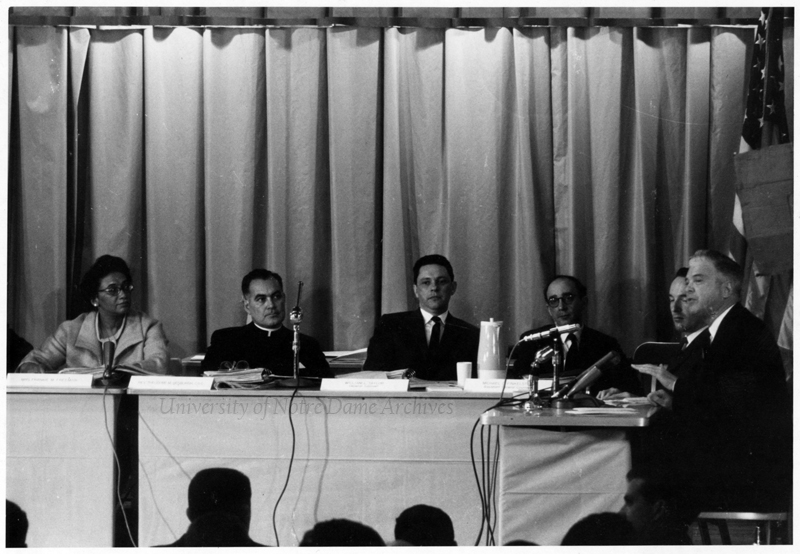

Caption

Source: University of Notre Dame Archives.

Mississippi Hearing

Father Hesburgh Takes a Stand

In the early to mid-1960s, the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights was preparing for a hearing in Mississippi, expected to be its most challenging to date. The commission was asked to postpone for different reasons, first by President John F. Kennedy, then by Attorney General Robert Kennedy, followed by his successor. In 1964, the newly sworn in attorney general asked the commission once again to call off their hearing due to a civil rights case receiving national attention. The commission chair, John Hannah, deferred to Father Hesburgh. "Father Ted, what do you think of that proposition?"

Well, the Attorney General was just sworn in, and he took an oath to follow the constitution. I recall that when we were sworn in we took an oath too to follow the constitution and the particular law governing this commission. The law says that if we have a certain number of complaints about voting, particularly, we have to have a public hearing and look into the matter. We have had more complaints from Mississippi than any state in the union. ... I say it's high time we follow our oath the way he's following his. ... If we don't get this hearing through, we're likely not to get a voting rights act. And if we don't get a voting rights act, it's going to affect more than that law case. It's going to affect the whole future of this country. So I for one say, respectfully for the attorney general, thanks for the advice but this time we're going ahead. We can't let our witnesses down a third time. It's just inhuman.

One by one, every commissioner responded, "I agree with Father Ted." And so, finally, in early 1965, they were able to move forward with the Mississippi hearing.

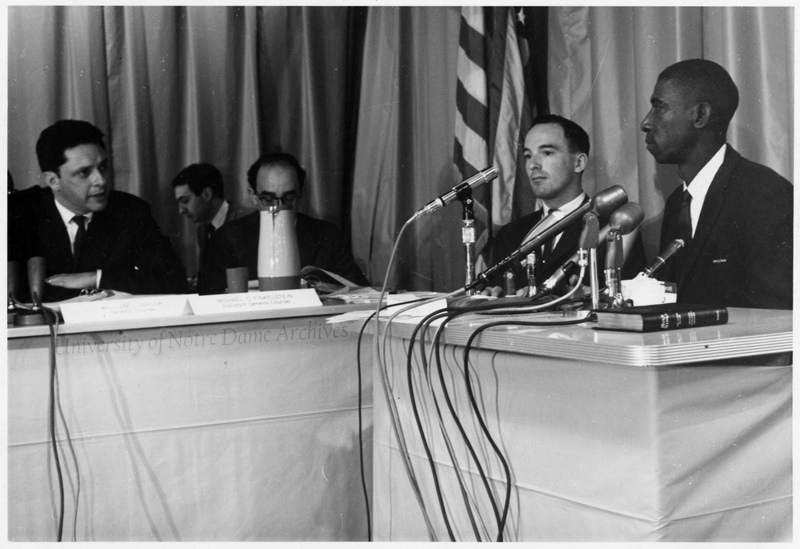

Source: University of Notre Dame Archives.

Moving Testimony

Televised nationally, Father Hesburgh was moved by African-American's testimonies. When a young, black farmer, Jesse James Brewer, was on the stand, Father Hesburgh asked him about his experience trying to vote. Brewer explained that he had been chased around town from county to county and then to the sheriff's office, trying to vote but was refused, then threatened, and even shot at. He shared that when he was in the army, he could vote but once home in Mississippi, he couldn't. When Brewer's two younger brothers came to visit, one lost an eye, and another got a fractured skull because the first didn't address "a white man" as "sir" when ordering soft drinks at a local store. The sheriff only scolded the men for causing trouble. Brewer said to Father Hesburgh, "At that point I thought I'd like to have a vote for who is sheriff around here."

Source: University of Notre Dame Archives.

Six months after the Mississippi hearing, and following much violence in the South, including the Selma to Montgomery marches, involving the "Bloody Sunday" attack of peaceful protesters by local and state police in Alabama, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which would protect the voting rights of all U.S. citizens and regulate elections.

Source: Lyndon B. Johnson Presidential Library.

Ideal Man for the Job

During the course of his tenure on the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, Father Hesburgh became increasingly impassioned about civil rights. He was deeply moved by personal accounts of bigotry and hatred, and recalled many stories with great clarity decades later.

It was clearly not by accident that President Eisenhower selected Father Hesburgh for the commission, nor that he continued to serve under the next three presidents. The work required a strong, moral presence and a person who was not afraid to stand up for the truth, no matter how great the opposition.